A Brief Reflection on Thinking Against the Archive of Puertorriqueñidad

By Jorell Meléndez-Badillo

To J. Kēhaulani Kauanui,

Theresa Warburton, and

William C. Anderson

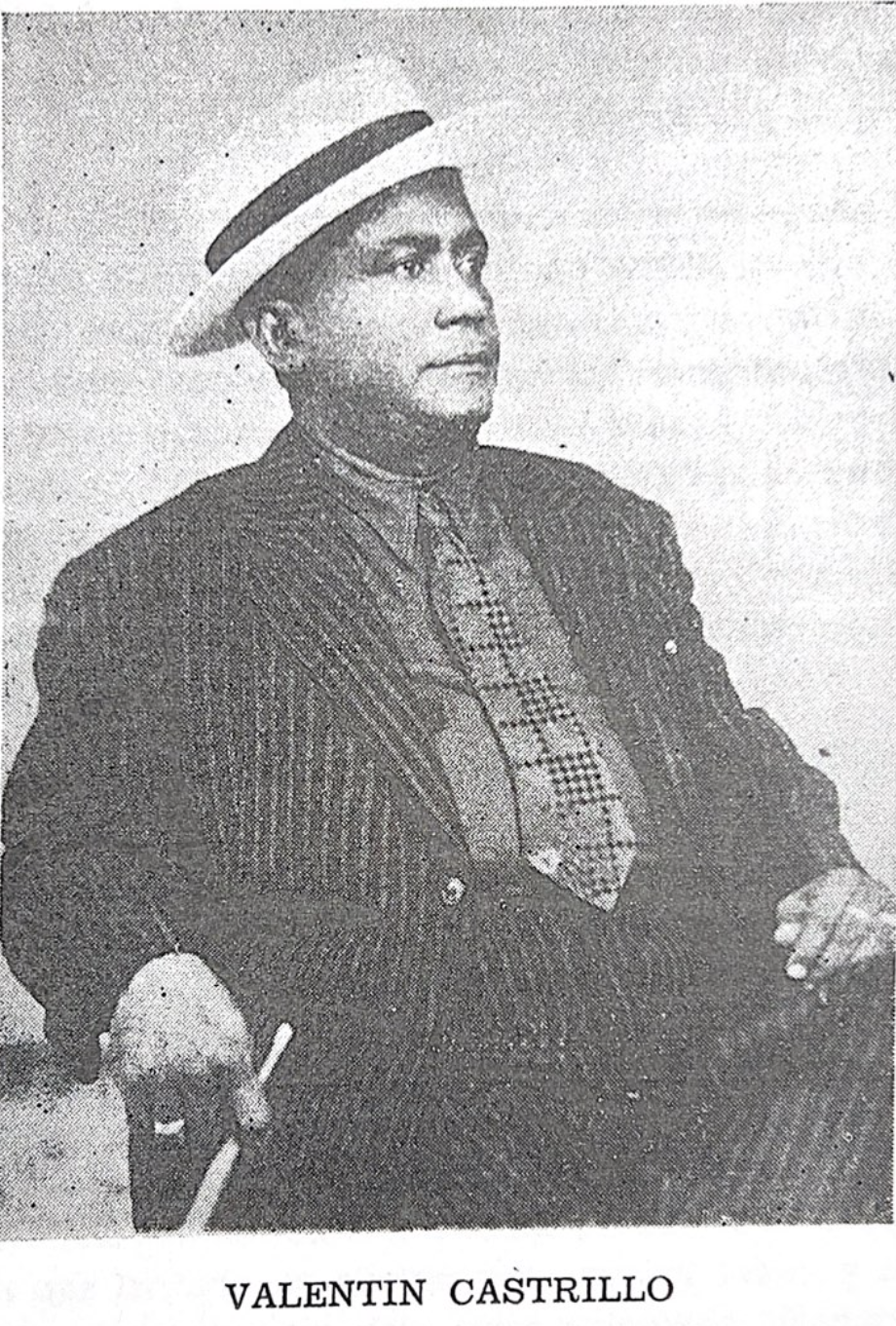

Over a decade ago, I found myself in a small municipal archive in the town of Caguas, Puerto Rico. I was conducting research on the archipelago’s anarchist history. The head archivist, the late historian Juan David Hernández, suggested that I read the working-class account of Valentín Castrillo’s Mis experiencias a través de cincuenta años. The book was part of a broader Puerto Rican radical print tradition of editing volumes composed of newspaper clippings, fragmented pieces of writings, and institutional records. Castrillo’s book served as an archive for his reflections and of reprints from El combate: Periódico defensor del pueblo y de la raza de color, a newspaper he edited from 1928 until well into the 1960s.

The book while interesting was not what I was looking for at that time. In its pages, Castrillo was not advocating for revolution, free love, or abolition. Instead, he was a proud member of the Socialist Party – whose leadership supported the annexation of Puerto Rico to the United States. My initial reading of the text was framed through a lens that understood radical politics within a firm binary of resistance or integration to US Empire. This gaze overlooked the other ways the book challenged contemporaneous white supremacist logics. Castrillo was a Black self-taught cigarmaker that carved a space within Puerto Rico’s world of letters, even if the position he occupied was marginalized.

My book on Puerto Rican anarchism, Voces libertarias, did not fully engage Castrillo’s work because it did not fit the epistemological boundaries of anarchist or labor radicalism. Not questioning the racial and heteropatriarchal logics reproduced in early-twentieth-century anarchist discourse in Puerto Rico, Voces libertarias instead replicated codes and logics that erased people like Castrillo from labor’s historical narratives. After the publication of the book, I continued to explore the cultural and intellectual worlds that working-class peoples created in the archipelago. I later read Ileana Rodríguez-Silva’s tour-de-force, Silencing Race, which pushed me to reconceptualize the place (or absence) of race and Blackness in my own work. I was particularly struck by how historians, even from the most radical traditions often reproduced master codes that erased individuals and communities. [1]

The production of historical knowledge entails reading with and against the archive. The copy of Castrillo’s Mis experiencias that I consulted during the research for Voces libertarias was housed at the Rare Books Collection in the José M. Lázaro Library at the University of Puerto Rico’s Río Piedras campus. While conducting my graduate work at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, I requested an interlibrary loan of the book from Boston College, one of the few institutions in the world that carries a copy. A handwritten note from its author offered me a new lens to interpret its pages. Castrillo wrote:

“Dedicated to Chestnut Hill: Boston College Library Massachusetts. Valentín Castrillo Box 511, Caguas, P.R. Después de leer este libro hagame [sic] el favor de darme su opinión. Estoy terminando el segundo tomo. Gracias.”

It is highly unlikely that the Bapst Library at Boston College had ordered a copy of this self-published book by a working-class intellectual in Puerto Rico. Instead, the note suggests a conscious attempt to be included in the archive, and to engage in dialogue with its readers. It seems possible that Castrillo found the address and sent the book because it might have been important for him to be part of its catalog. Just like the book’s content served as a carefully crafted archive, the note demonstrates Castrillo’s intention of going against the logics that erased Black working-class intellectuals from Puerto Rican history. The note, then, can be read as a refusal to be erased. A refusal to be silenced. A forceful irruption into the archive.

En estos años largos años de estar defendiendo Los Derechos del Pueblo y de la raza de Color, no he recibido cooperación económica ni intelectual de los que estan en la obligación de ayudar al único periódico de sabor obrero y fiel exponente de los derechos de la raza de color, que no camina por los tortuosos caminos del adulamiento ni traiciones.

Translation:

In these long years of defending the Rights of the People and of the Colored race, I have not received economic or intellectual support from those who are obliged to help the only newspaper with a working-class flavor and a faithful exponent of the rights of the colored race that does not walk the tortuous paths of flattery or betrayal.

Mis experiencias, p. 33

Valentín Castrillo dedicated his life to both the Socialist Party and to the advancement of Black people in Puerto Rico. Why is he absent from the archipelago’s historical narratives? His newspaper, El combate, ran for more than three decades—an impressive feat for any newspaper in Puerto Rico, not just working-class publications. Why do we only have a few scattered numbers archived? I suspect that the answer to these questions lay in the ways that the archive of puertorriqueñidad operates.

In dialogue with Lorgia García Peña’s work in The Borders of Dominicanidad, I argue that nineteenth-century liberal intellectuals built the archive of puertorriqueñidad through “historical documents, literary texts, monuments, and cultural representations sustaining national ideology” (12). By archive, I am not simply referring to physical repositories but, following Antoinette Burton in Archive Stories, “to traces of the past that are collected either intentionally or haphazardly as ‘evidence’” (3). A national archive is composed of all the documents and the discourses within them that sustain the idea of the nation as constructed by dominant political ideologies. The archive of puertorriqueñidad dictates who is deserving of belonging to the nation. It establishes the limits on what can be said about the nation and what (or who) is left outside of it. Moreover, this national archive organizes the ways people imagine puertorriqueñidad by perpetuating racial democracy myths.

However, the archive of puertorriqueñidad is also composed of multiple minor archives that compete to be integrated into the nation, or to modify it. The working-class intellectual archives of early twentieth-century Puerto Rico, for example, were minor archives. They were minor both in relation to the production of sources by major institutions and because the knowledges contained within its pages were understood as lesser.

Working-class archives, however, did not challenge—but often reproduced—the racial, patriarchal, and Eurocentric logics of puertorriqueñidad. As minor archives, working-class collections also created silences and subjugated particular knowledges. The obreros ilustrados I have followed in my book, The Lettered Barriada, did not simply ignore Blackness and workingwomen. They actively erased them from the historical record. But within those minor archives, we also find counterarchives. Those archives that were produced through the logic of refusing to be erased or silenced. Counterarchives thus defy the silencing logics of both minor and national archives through acts of refusal.

Valentín Castrillo’s Mis experiencias functions as a counterarchive. Its pages did not reproduce the radical theories in vogue at the time among anarchists and communists, but it challenged the racial democracy myths that gave way to the idea of puertorriqueñidad. As Yomaira Figueroa Vázquez notes, Boricuas, and particularly Afro-Boricuas, are a “paperless” people. Yet, Castrillo refused to become paperless by publishing his newspaper and books. [2] He also refused to be paperless by placing his book in an archive with the hopes of its circulation.

The erasure of working-class intellectuals and women that took place at the beginning of the twentieth century still carries power today. That is why we do not know much about people like Valentín Castrillo. We also do not know much about Paca Escabí, a Black laundress that organized workers in the Western town of Mayagüez, or José A. Lanauze Rolón, a Howard-educated Black physician from the Southern town of Ponce that helped found the Communist Party in Puerto Rico. There are so many that we might never know about.

The idea of the Puerto Rican nation is not geographically bounded to the Caribbean but also includes the global diaspora. Because the archive of puertorriqueñidad also operates beyond the archipelago, the intersections of racism, imperialism, sexism, and other systems of oppression continue to perpetuate these erasures transnationally. That is why people like Martín Ramírez Sostre—one of the pillars of Black anarchist thought and action— are absent from radical discourses of puertorriqueñidad. [3]

To read against the archive of puertorriqueñidad entails questioning and shedding light on the logics that perpetuate erasure, silencing practices, and epistemic violence. My intentions are not to incorporate Castrillo, Sostre, Escabí, or Lanauze Rolón into an archive, but to transgress the limits of our historical thinking by creating transhistorical conversations with those who the archive has conspired to keep us from engaging with. This entails undisciplined readings that pay attention to subtle ruptures and refusals, even if they appear in the form of a simple handwritten note.

Notes

[1] See Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, “Mateo and Juan: Racial Silencing, Epistemic Violence, and Counterarchives in Puerto Rican Labor History,” International Labor and Working-Class History vol. 96 (Fall 2019): 103-121.

[2] Yomaira Figueroa Vázquez, “Afro-Boricua Archives: Paperless People and Photo/Poetics as Resistance,” Post45 (January 21, 2020).

[3] For more on Sostre, see The Martin Sostre Institute.

References

Burton, Antoinette, ed. Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

Castrillo, Valentin. Mis experiencias a través de cincuenta años. Caguas: N.p., 1952.

García Peña, Lorgia. The Borders of Dominicanidad: Race, Nations, and Archives of Contradictions. Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

Meléndez-Badillo, Jorell. Voces libertarias: Los orígenes del anarquismo en Puerto Rico. Fundación de Estudios Libertarios Anselmo Lorenzo, 2014.

Meléndez-Badillo, Jorell. The Lettered Barriada: Workers, Archival Power, and the Politics of Knowledge in Puerto Rico. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Rodríguez-Silva, Ileana. Silencing Race: Disentangling Blackness, Colonialism, and National Identities in Puerto Rico. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Cover Photo Credit: Socialist Party’s executive committee (c. 1924) - Distorted Image.

Dr. Jorell Meléndez-Badillo is currently an Assistant Professor of History at Dartmouth College and incoming Assistant Professor of Latin American and Caribbean History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His work focuses on the global circulation of radical ideas from the standpoint of working-class intellectual communities in the Caribbean and Latin America. His most recent books are The Lettered Barriada: Workers, Archival Power, and the Politics of Knowledge in Puerto Rico (Duke UP, 2021) and Páginas libres: Breve antología del pensamiento anarquista en Puerto Rico (Editora Educación Emergente, 2021). He is currently completing a book titled Puerto Rico: A National History for Princeton University Press.