“Cuz we got our own white people”: Black Looks, Latinx Bodies

By Armando García

I.

The comedian, Aida Rodriguez, appeared on Comedy Central’s Hell of a Week in November 2022 to discuss U.S. midterm elections results with the show’s host, Charlamagne tha God. At the start of the conversation, Charlamagne posed a critical question: “So why does the Latino vote differ so much from the Black vote?” Importantly, this question repeats a narrow conception of race often used in discussions that erupt whenever minoritized communities vote against their best interests. Still, the exchange between Rodriguez and Charlamagne strikes me for other reasons. The language of the question indexes Blackness and Latinidad in binary terms when it suggests that both communities are antithetical to one another because many Latinx voters supported the Republican Party, whereas Black voters largely voted Democrat. It likewise suggests that Latinidad and Blackness are incommensurable categories whose boundaries cannot overlap. Charlamagne assumes that that Black people cannot be Latinx and that, in voting conservatively, Latinxs are akin to the white voters aligned with white supremacy. Rodriguez’s response also reifies this logic:

Cuz we got our own white people and people don’t understand that, that the assimilation possibility for Latinx, Latine, Latin people is higher. People can come from different parts of Latin America, marry white, as like they are told to, assimilate, and assume a white identity that Black people cannot escape from. So they will continue to vote in that way because to them that’s upward mobility, and unfortunately for us success means being patted on the back—not all of us…—but they get the pat on the back from white people and they feel like that’s what being American is. And that colorism is real in our communities, it is real…

This response was then shared by Rodriguez on Instagram, where many users (me included) commended her for her analysis of race and Latinidad. She was also trolled by others. One user lashed out against her for “being flat ou[t] racist towards white people everywhere,” to which Rodriguez retorted that the user themselves was racist because their own comment “erase[d] black Latinos from the conversation.” While one could argue that Rodriguez’s response has the potential to erase Black Latinxs by discussing Latinidad solely through whiteness, it is important to note that her analysis is arguably framed by the question’s terms. Charlamagne leaves no space to account for nonwhite Latinxs, and he does not think of Latinidad outside of antiblackness. Rodriguez was prompted to discuss Latinidad as white supremacist because the question itself defined Latinidad as antiblack from the start.

The conversation offers us the opportunity to interrogate the racial and racist logics that pit Latinidad and Blackness against the other. These discourses are so pervasive that even two prominent public figures like Rodriguez and Charlamagne fall into the trap set up by the logics they want to resist. [1] They engaged in their conversation because they sought to understand the discourses and ideologies that shape minoritized communities, hoping that, in understanding them, that they could work toward resisting racism. Rodriguez’s analysis rightly points to antiblack figurations of Latinidad. What strikes me is that, in their attempt to understand the divergence between Latinx and Black communities, they reinforced this divergence by discussing Latinidad as incommensurable with Blackness. Rodriguez herself is Afro-Indigenous Latina, and her retort on Instagram demonstrates that she is not blind to Black Latinidad. At the same time, her exchange with Charlamagne also shows us what happens when we fail to index Latinidad as also Black. The conversation left AfroLatinxs out of the question.

Latinidad poses a problem for binary racial discourses because Latinxs are a heterogenous people who are not homogenously racialized. As a case in point, Rodriguez’s and Charlamagne’s exchange illustrates the problems that arise when an ethnicity is defined explicitly as a racial identity. Popular discourses, both in the media and in academic scholarship, are so fixed on seeing Latinidad as a marker of racial difference that they often ignore that Latinidad is an ethnic identity, not a racial one. [2] Race and ethnicity are not synonymous. Hence, just like there are white Latinxs, there are also Brown and Black Latinxs. Colorism is real, and Latinxs, like other minoritized communities, are racialized the minute the gaze of the other fixates and brands bodies with an identity based on the color of their skin and other physical features. Latinxs are thus not inherently antiblack. As Rodriguez argues, the impetus for assimilation aims to align everyone with antiblackness to gain recognition from the white gaze (“but they get the pat on the back from white people”).

II.

In thinking with Rodriguez, I want to interrogate the moments where minoritized artists lack the adequate language to see Black Latinx bodies as Black Latinidad. Rendering Latinidad through narrow definitions of race makes it impossible to see Latinxs’ antiracist possibilities. But can race and Latinidad be mapped otherwise? Rodriguez’s response shows us that we ought to examine the insidious ways that white supremacy can shape how minoritized communities see each other and themselves. If race is determined through visuality, then antiracist projects must avow visuality as a potential site of liberation. [3]

Rather than dismissing Latinidad as inherently antiblack, I am more concerned with understanding what happens when Latinx artists do envision Latinidad through Blackness. Artistic practices that account for Black Latinidad are framed by an antiracist imaginary that can potentially alter how we see race and Latinidad. I was first prompted to consider this racial imaginary in Fur (2000), a play by the Nuyorican playwright, Migdalia Cruz. The play’s three characters are Citrona, a young woman whose body is covered in black hair; Michael, an older man who buys Citrona from a carnival show and imprisons her inside a cage in his pet shop; and Nena, a hairless woman whom Michael hires to feed Citrona.

None of the characters are given an ethnic identity in the play, but Cruz’s notes on Fur identify Citrona as Latina. [4] We can assume that Nena is likely Latina because of her Hispanic name, but Michael is not ethnically identified. The characters’ racial identities are not clearly identified in the play either. However, even if the playwright does not give them a racial identity, the characters racialize each other. Citrona, Nena, and Michael relate to each other based on how they see Citrona’s hair and Michael’s skin. Michael desires Citrona’s black hirsute body because he sees her as “a beauty covering her naked flesh in black tresses” (Fur, 108). In this way, he racializes her as Black. Moreover, Nena is repulsed by Citrona because she thinks “[she’s] a beast” (110), and she pines after Michael because “he’s a different kind of white” (79). Nena is also described as Citrona’s physical opposite, and since she sees Michael as a different type of white person than her, she’s racialized as white as well. Citrona wants Nena, whom she loves, to see that Citrona is not like the animals she eats: “I’m white inside” (87), she tells her. She wants Nena to see her as human and as white as her. By the end of the play, Citrona eats them both when they refuse to recognize her humanity. They may lust after one another, but since the social relations between them are designed through racism, Citrona frees herself of Michael’s and Nena’s white gaze.

Fur functions as an antiracist script in that it is a representation of racialized humanism that liberates the oppressed. However, Fur’s production history tells a different story. The play does not describe Citrona wearing clothes, so the other characters and the audiences cannot avoid but look at her nude body covered in black hair. Citrona’s Blackness is arguably the central piece of the story since Michael’s and Nena’s gaze determines that she is unworthy of human meaning because of her black hirsute body. Citrona is not identified in the play as being of African ancestry, so I am not reading her as Black because of lineage. Nor do I think she should be read as a Black woman because she is covered in black-colored hair. Citrona’s Blackness is not determined by her hair color, but by the gaze of the other (white) characters who see her hirsute body as a marker of her subhumanism and animality. Michael and Nena don’t simply look at her and see black hair, they look at Citrona’s black-colored hairy body and see a Black woman/beast because of it. [5]

I’ve researched images from Fur’s productions for over a decade, and to my knowledge, only one company has cast a Black actor, and none used costuming that resembles Citrona’s character description. Most productions cast a light-skinned/white actor in the role. They sometimes fully cover the actors’ body in a white or light-colored costume, or rather than covering their bodies with hair, they use costumes with patches of black hair that do not hide the actor’s light-colored skin. The point for these productions, it seems, is to make Citrona appear as white as possible so that the audience will not see the Latina woman on stage as a Black hairy woman. [6]

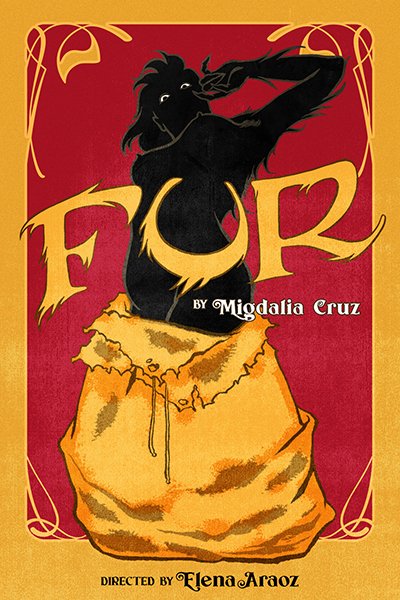

I attended a production of Fur in 2019, this time by New York City’s Boundless Theatre Company. The production cast a light-skinned, light-haired actor to play Citrona, and costumed her with a bodysuit that was only partially covered in black hair and showed much of her skin. These casting and costume decisions contrast sharply with the image used in the poster advertising the show (Figure 1). The image in the poster illustrates the moment when Citrona first enters the stage as “a large, unseen animal in a sack” (78). But the Citrona of the poster is not unseen. She is a black female figure with a hairy body and sharp fingernails, and she has broken out of the sack to look directly at us.

[Figure 1. Boundless Theatre Company, Fur, 2019]

Casting and costume decisions control what audiences see on stage and how we look at the performers. Envisioning Citrona on stage in the body of a light-skinned/white actor—Latina/x or otherwise—or costuming actors with clothes that hide Citrona’s black hirsute body or simply packages it through lighter skin/fur, limits the audiences’ ability to see her as Black or, by extension, to see Latinxs as Black people. Regardless of the theater producers’ intentions, their decisions represent Latinidad as only white and discard its Black and Brown possibilities. [7] Like Charlamagne’s question, they, too, risk mapping Latinidad solely through white supremacy and antiblackness.

Theatrical representations have thus rendered Fur’s antiracist potential obsolete because they do not allow the audiences to fully see Citrona’s Blackness. And yet, Citrona’s Black Latinidad and Fur’s liberatory potential cannot be denied. At the end of the play, Citrona eats the white (Latino?) man and the hairless, white Latina who prove blind to her humanity. Free of physical bondage to her masters, Citrona is also free to see herself beyond their white gaze. She shows us that we must understand how white supremacy attempts to blind us all, and perhaps then we will be able to refuse its gaze by looking at Latinidad and seeing race beyond its binary renditions.

Notes

[1] Rodriguez has spoked widely about race and Latinx communities through her stand-up comedy and public interviews. Besides hosting Hell of a Week, Charlamagne tha God is the co-host of the popular radio show, The Breakfast Club, and is notorious for his controversial commentary on race, politics, and pop culture. See Rodriguez’s HBO special, Fighting Words (2021); Tina Sampay. “Aida Rodriguez On Why Latinos Don’t Claim Blackness, Paul Mooney, Black Comedy, Mixed Family & More.” Comedy Hype, April 8, 2023; and Rachelle Hampton. “The Voice of Black America? How the white political establishment anointed Charlamagne tha God as the spokesman for all Black voters.” Slate, November 30, 2020.

[2] Lorgia García Peña’s theorization of Black Latinidad offers a more expansive discussion of race and Latinidad. See Lorgia García Peña. Translating Blackness: Latinx Colonialities in Global Perspective. Durham: Duke University Press, 2022.

[3] My analysis of race and visuality here draws from Frantz Fanon. Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. Charles Lam Markmann. New York: Grove Press, 1967, and Nicholas Mirzoeff. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

[4] See Migdalia Cruz. “The Writer Speaks.” Out of the Fringe: Contemporary Latina/Latino Theatre and Performance. Eds. Caridad Svich and María Teresa Marrero, 72-73. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2000.

[5] Citrona is exhibited in a carnival show at the start of the play, but even after Michael purchases her and removes her from the show/exhibition, he continues treating her as a “freak” on display by imprisoning her in a cage. He also watches Citrona in every scene, often without her knowing. Fur can thus be read as an allegory of the forced exhibition of people from Africa, Asia, and the Americas who were displayed as “freaks” throughout the U.S. and Europe. Coco Fusco discusses the long history of forced exhibitions in her seminal essay, “The Other History of Intercultural Performance.” TDR 38-1 (Spring 1994): 143-167.

[6] San Francisco’s Campo Santo produced Fur in 1997 under the direction of Roberto Gutiérrez Varea, who cast the Afro-Venezuelan actor, Greta Sánchez-Ramírez, as Citrona. Images from the production illustrate a certain uneasiness with allowing the audience to fully see Citrona’s Blackness. Sánchez-Ramírez appears seemingly nude in some scenes, with patches of black curly hair appearing on her body but not on her face. The hairlessness of her face contrasts with the black hair on her body. She also appears fully clothed in other scenes where she wears a white costume covering her up to the neck. The costume hides Citrona’s hairy body, and its white color contrasts sharply with her hairless face.

[7] As an entry point for these possibilities, see Claudia Milian. Latining America: Black-Brown Passages and the Coloring of Latino/a Studies. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2013.

References

Comedy Central. “Midterm Ejection.” Hell of a Week with Charlamagne tha God. November 10, 2022.

Cruz, Migdalia. “Fur.” Out of the Fringe: Contemporary Latina/Latino Theatre and Performance. Eds. Caridad Svich and María Teresa Marrero, 71-113. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 2000.

Dr. Armando García is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of California, Riverside, where he specializes in Latinx and Latin American literature, theatre, performance studies, and visual culture. He is completing his first book, Impossible Indians: Decolonial Performances of Indigeneity, a study of decolonial aesthetic practices and temporal figurations of Indigenous humanism. His work appears in Social Text, Modern Drama, and Critical Philosophy of Race.