Blues Women & Idlewild Archives

By Tacuma Peters

There is something about Angela Y. Davis’s Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude ‘Ma’ Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday that I have been unable to shake. Seven years ago, it introduced me to the performers Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, and provided me with a deeper appreciation of the cultural and political critiques of Billie Holiday. Davis’s text examines the ways in which the lyrics, performances, appearances, and actions of these performers articulated and shaped a working-class consciousness that embodied a complex tradition of Black feminist theorizing. The book provides a rich history and philosophical reflections on the social, political, and economic contexts of the artists and the communities that they emerged from and served. It also positions Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday as philosophical, political, and cultural agents who challenged the epistemologies and structures that Black women encountered when seeking bodily autonomy, socio-political freedom, and affirmation of their lived experiences in contexts that were shaped by patriarchal, classist, racist, and homophobic norms and structures.

[Ma Rainey Georgia Jazz Band, c 1924-25]

Since first reading Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, it has been difficult to listen to Bessie Smith's “Backwater Blues” and not think about climate change in the Caribbean, especially the devastations of Hurricanes Maria and Dorian, the flooding of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, or the many other natural/colonial disasters. [1] The same for such connections as “Jailhouse Blues” which fits neatly with the long history of African American incarceration in the U.S. after emancipation; “Prove It On Me Blues” which highlights the pleasures and persecutions of Black lesbian desires and night life. [2] And doubly and triply so for Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” which always evoke not only the murder of Black women, men, and children at the hands of law enforcement and vigilantes, but also the myriad racist incidents that are enacted on people racialized as non-white within the United States and throughout its empire. The obviousness of such connections does not dull their power nor limit the songs theoretical and affective possibilities.

However, this exploration is not about whether the blues is a better lens for interpreting black life over other Black diasporic cultural forms from the Caribbean, South America, North America, Africa, Europe, and elsewhere. Nor is it a claim that Black cultural production springs from instinct or natural inclination, for black creativity is a consequence of “assembly, not birth.” [3] Instead, this piece functions as a simple reminder that the cultural production of those in the African diaspora have the power to illuminate existence, political structures, social phenomena, as well as philosophy in unique and productive ways.

The blues is more than just a musical genre, it grounds us in specific realities. The blues expresses existential perspectives regarding the irrationality and unfairness of existence, as well as the particular modes of existential anxiety and being that are experienced by Black women, men, and children in an unjust and violent racist world. However, as Billie Holiday once noted in her 1957 performance of ‘Fine And Mellow’: “There’s two kinds of blues, the happy blues and then sad blues.” Commentators and artists have long noted that the blues is an elastic form that can express a vast range of emotions and states of being.

There is little chance that the importance of the blues as a framework for understanding the world will be lost or forgotten. [4] However, it might be important to remind ourselves that it is yet another resource that has been left by our ancestors. It is a vast archive of recordings, sheet music, and improvisations. It is the wisdom held by the multitude of interpretations that poets, novelists, dramatists, visual artists, activists, public intellectuals, academics, and others have provided over the past century and a half. As such, it might tell us something about facile liberal democratic notions of history as progress, development, and the transcendence of the past. This music form—and philosophical stance—hundreds of years old may prevent us from falling into the trap of teleological understandings of history, including the histories of black cultural production, in which newer is de facto better. Furthermore, it might challenge us to query our own implicit beliefs that novelty gives us little reason to dwell on forms, philosophies, ways of being, and artistic creations that have been superseded.

I have a vested interest in rejecting teleological beliefs of progress and success. Seven years ago, my grandmother, Laverne Davis, gifted me my grandfather’s vast record collection of jazz and blues 78s and LPs for caretaking purposes. Soon afterwards, I spent a year building a website that traced the history of my grandfather Jack Davis’s archive—including his be-bop, swing, gospel, and blues 78s. These were shellac artifacts that held the lives and histories of the maternal side of my family spanning four generations. Amongst the recordings were 78s from the 1920s including Bessie Smith, Mamie Smith, Ma Rainey, and other blues and jazz artists from when he was a child. These records were likely purchased by his father—a musician—his mother, and grandmother.

[U.S.S. Mason enlisted black crewman - Jack Davis (Left), 20 March 1944]

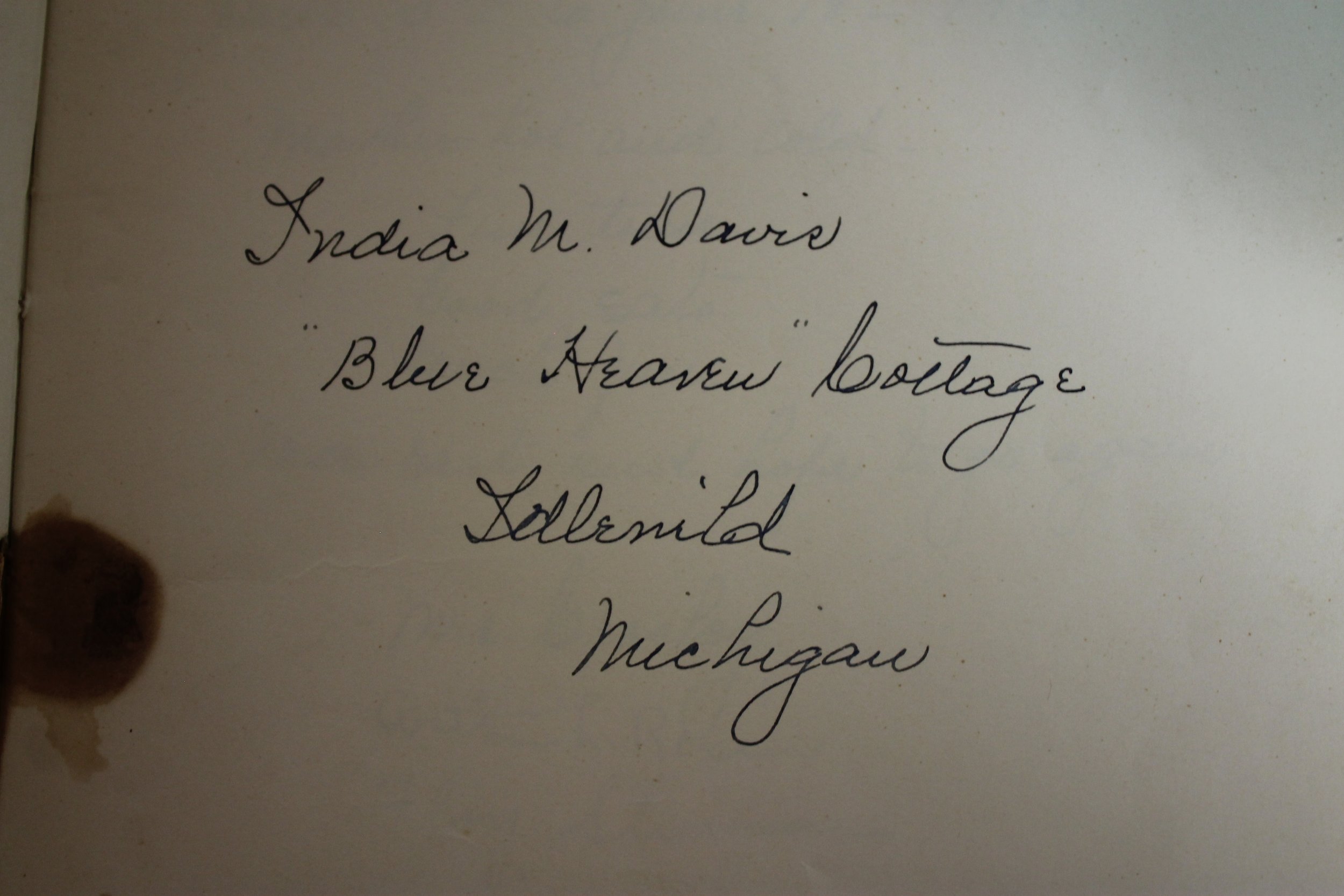

The digital humanities website that I crafted featured articles about my grandfather’s time on the U.S.S. Mason (an all-Black WWII navy vessel), pictures and stories about how my great-great-grandmother India (a domestic worker in Indianapolis) secured a loan from her white employer to buy two lots and build a cottage she named “Blue Heaven” in the all-Black resort town of Idlewild, MI in 1933. The site contains an oral history of my grandmother that explained her childhood in Grand Rapids, her labor activism when working for Bell, and her life with my grandfather, and finally it holds a discography of my grandfather’s 78s and audio of some of the records. Yet even with all this work, I never published the website. The only trace of this archive on the internet is this paragraph, nestled into this discussion, and like the blues (and other black diasporic productions)…this too is enough.

[First page, Guest Book for “Blue Heaven” Cottage]

It is important to not be seduced by understandings of originality, novelty, and individual achievement, all deeply colonial logics. [5] And it may be an odd sentiment to want to share the blues, and yet, I invite us to consider – for at least a few moments — what Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday help us understand about our lived experiences, our family histories, and our collective existence. This includes, the demands and vicissitudes of love, the transience of joy and misery, the dialectics of celebration and mourning, and the contingencies and structures of existence that are much too large for the will of a single individual. These works also highlight the creativity, philosophical sophistication, consciousness, assertiveness, and world-building and relation building capacities of those who are demonized, dismissed, exploited, and violated by the more powerful. The blues and Davis’s stellar book attest to the possibilities of creating with others: “How lovely it is, this thing that we have done— together.” [6] I invite those who have not read it, or who have forgotten its contents, to grab a copy of Angela Y. Davis’s book. There is so much that we can do when we take Black women, blues women, and our collective histories as points of departure in our lives and work.

Notes

[1] Yarimar Bonilla, Aftershocks of Disasters: Puerto Rico Before and After the Storm (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019).

[2] Out in the Night (Dir: Blair Doroshwalther, 2014).

[3] Paul C. Taylor, Black Is Beautiful: A Philosophy of Black Aesthetics (Malden: Wiley, 2016).

[4] Of note are the works of Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Toni Cade Bambara, Sonia Sanchez, August Wilson, Gayl Jones, and innumerable others.

[5] Kristie Dotson, “Between Rocks and Hard Places: Introducing Black Feminist Professional Philosophy” The Black Scholar: Journal of Black Studies and Research Vol. 46 no. 2 (2016): 46-56.

[6] Toni Morrison, “The Nobel Lecture in Literature” What Moves at the Margins: Selected Nonfiction (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 207.

References

Davis, Angela. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. New York: Vintage, 1999.

Morrison, Toni. “The Nobel Lecture in Literature” What Moves at the Margins: Selected Nonfiction. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 207.

Taylor, Paul C. Black Is Beautiful: A Philosophy of Black Aesthetics. Malden: Wiley, 2016.

Cover Photo Credit: Elizabeth Catlett, “I Have Given the World My Song” (1947).

Dr. Tacuma Peters is an Assistant Professor of Black Political Thought and Philosophy in the Political Theory and Constitutional Democracy major of James Madison College and in the Department of Philosophy at Michigan State University. His teaching and research are focused on the history of political thought and contemporary political philosophy as it relates to chattel slavery, European empire, and decolonization.

![[Carl Van Vechten, “Bessie Smith,” 1936]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fc7fe3cba91e34ba34df9bf/1645654298514-X8HDM75WVGYWY49QNO2B/Bessie+Smith+Smithsonian.jpeg)

![[Herman Leonard, "Billie Holiday," 1949]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fc7fe3cba91e34ba34df9bf/1645654298536-9MW31EJSSOME2PKGJL33/Billie+Holiday+Smithsonian.jpeg)