Colectivo Ayllu: A Practice of Liberation For

By Vialcary Crisóstomo Tejada

“Is it possible to think— and by extension do—otherwise?”

- Lewis R. Gordon, Freedom, Justice, and Decolonization

In the epigraph that opens this text, Lewis R. Gordon ask us if it is possible to think and do otherwise. Although one might instinctively respond in the affirmative, one wonders how. How can we think and do differently? What must we change to create an otherwise? Decolonial thought [1] argues that an otherwise is contingent on a decolonial turn [2] that transgresses the colonial matrix of power and enables, as Catherine Walsh notes in “Decoloniality in/as Praxis,” other ways of “being, feeling, thinking, knowing, doing, and living” (20). In dialogue with the concept of coloniality of power, decolonial thought inquires into the ontological and epistemic legacy of colonialism while questioning Euromodern and universalist logics of knowing and being. [3] As a political and epistemic project, decoloniality calls for the transformation of the “historical-political-economic order,” [4] the abolition of the hierarchy of humanities established by coloniality, and the articulation of other ways of knowing and being to engender other worlds. In fact, Gordon’s question seems to find an answer in decolonial thought, insofar as elaborating of other epistemologies can create the conditions of possibility to think otherwise. Yet, we must still ask, how can this articulation be put into practice? How do we go from thinking to doing otherwise?

Here the artistic work of the Colectivo Ayllu stands as a testament to thinking and doing otherwise. By reading Ayllu’s work as a project of liberation for, I argue that this collective disrupts modern/colonial logics that make invisible and silence non-white and non-heteronormative subjects, while also enabling other conceptions of being and knowing, an otherwise.

Decoloniality & Liberation

In his book Freedom, Justice, and Decolonization (2020), Gordon argues that Euromodernity excludes other ways of knowing by posing its reason as universal, hence decolonization requires philosophy to transcend itself. In dialogue with the notion of decoloniality for, proposed by Catherine Walsh, [5] Gordon argues that decoloniality cannot only be the disarticulation of modern/colonial logic—decoloniality from—but also the articulation and construction of other ontologies and epistemologies—decoloniality for. Starting from this idea, Gordon introduces the concept of liberation for as one of the objectives of a decolonial turn. He argues that “political problems require political, not moralistic, solutions” (17) and that the articulation of a liberation for incites the production of political agency rather than making an appeal to morality. Gordon asserts that Euromodernity restricts those categorized as non-human, what Fanon called les damnés de la terre, from political life through four kinds of invisibilities: racial, temporal, vocal, and epistemic.

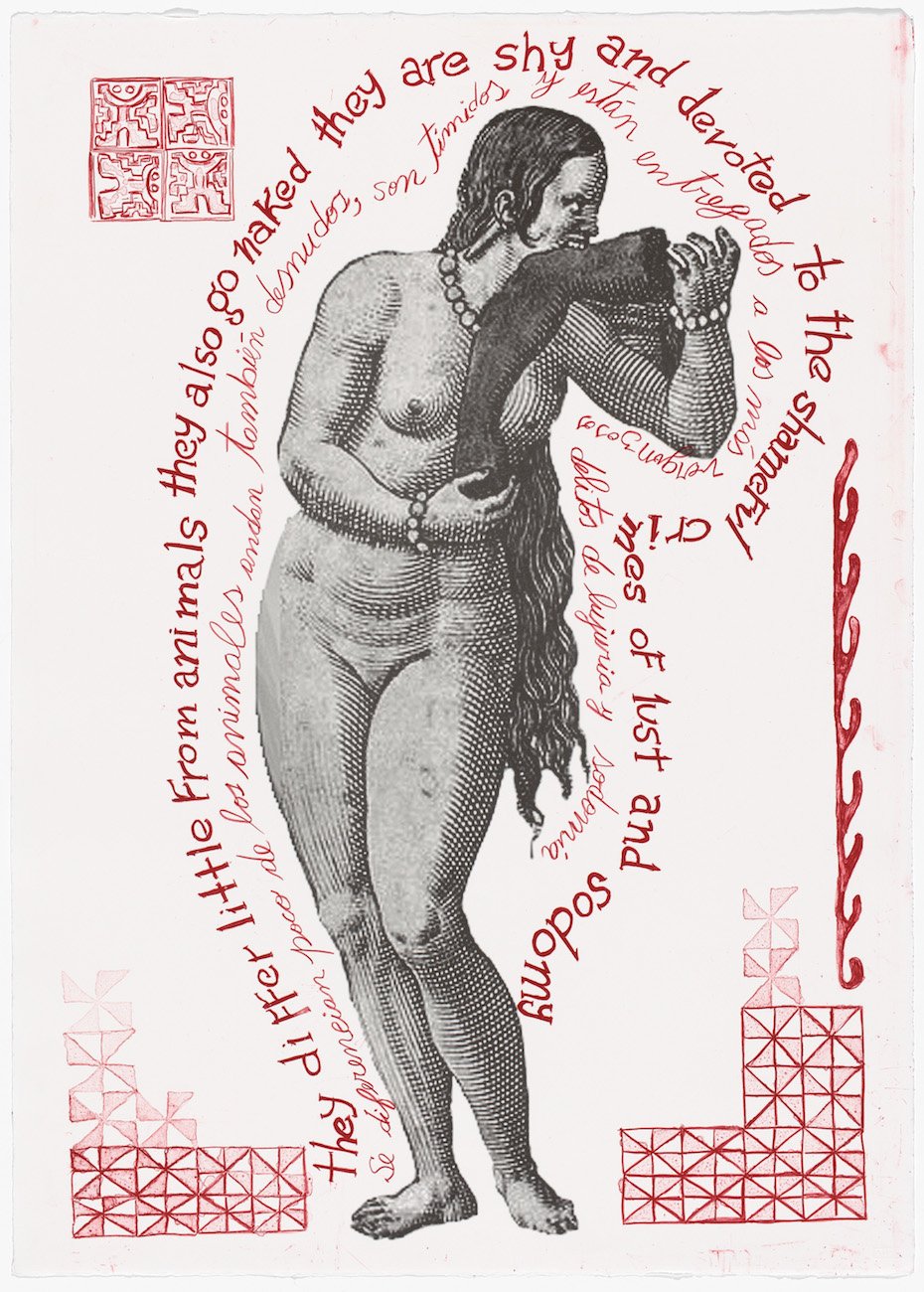

[Collective Ayllu, “El Caníbal (The Cannibal)” (2019)]

Racial invisibility narrates non-white subjects in quantitative terms and claims that “there is always ‘too many’” of them. [6] Temporal invisibility frames indigenous peoples as part of the past, and the white/colonizer as belonging to the future. Meanwhile, vocal invisibility, highlights the absence of voice for racialized, feminine, and non-heteronormative subjects and their failure to be heard. Lastly, epistemic invisibility denies and delegitimizes non-European knowledges. These invisibilities facilitate the erasure of the “non-human” as well as other ways of knowing thereby reducing or excluding the colonized other from participating in the production of power. A liberation for, as posited by Gordon, “is the rallying of creative resources of possibility” (23) to re-imagine normative life. Such possibilities could facilitate the elaboration of counter-hegemonic models of being and knowing.

By advancing a decolonial turn from the perspective of a liberation for, we articulate a political project that centers the construction of other worlds; worlds for the “no people who are always de trop in virtue of their race, barred from the future by virtue of being indigenous, voiceless because blocked from embodying political agency or citizenship by virtue of their gender or race, and excluded from the production and appearance of and contributing to knowledge” (24).

Ayllu’s Artistic Work and Liberation for

Starting from the conception of decoloniality in/as praxis, multiple feminist collectives have emerged in Abya Yala and its diaspora that propose a theoretical-political practice for thinking and doing otherwise. Among these collective we find the Colectivo Ayllu, founded by Latin-Americans Iki Yos Piña Narváez, Lucrecia Masson Córdoba, Francisco Godoy Vega, Kimy Leticia Rojas, and Alex Aguirre Sánchez in 2008 in Madrid. Ayllu defines itself as a “Collaborative artistic-political research and action group formed by migrant agents, racialized, sexual and gender dissidents from former colonies.” [7] Named after the Quechua concept Ayllu, meaning a community or non-biological family, the artistic-political work of the Colectivo Ayllu centers relationality, thinking and being in community.

Ayllu’s extensive work includes theoretical productions, artistic works, and pedagogical practices. [8, 9] For this reflection, I will focus on analyzing two examples of the collective’s artistic works, the map Corpografía and the installation don't blame us for what happened, which, I propose, materialize an artistic-political project of liberation for. I argue that by mapping the city from the margins of society, the erased ontologies and epistemologies, Ayllu’s artistic productions disrupts spatial-temporal framework through which we understand modernity as Euromodern, and by situating the wretched at the center and now of the metropolis they articulate other possibilities of being, thinking, knowing, and doing, other modernities.

[Gustavo Adolfo Díaz G (Collective Ayllu), “Corpografía: una ciudad, muchas fronteras” (2019)]

As part of its project “One city, many frontiers” at the Matadero Madrid, Ayllu created Corpografía, a non-map of Madrid’s cartography inhabited by poor, queer, non-white immigrants. By representing space in a racial, queer, socioeconomic, and migratory key, Corpografía places the non-white, non-heteronormative, immigrant and poor subject at the center of the metropolis and, therefore, reinscribes the subject previously erased and silenced from history in the present and future. Temporal invisibility aims to situate non-whites in the past and thus, not belonging to the future. However, in Corpografía, Ayllu defies this conception of time and space by situating along the same time-space, in the Madrid of today, the colonizer and the colonized; black and white; heterosexual and nonbinary.

In this other “map”, a map that recognizes that the city is figuratively and literally built on the bodies of the “other”, the invisibilities of Euromodernity are challenged by the non-white immigrants from Lavapiés, by a present with black and indigenous people in front of the statue of Columbus, by the sound of the heels of trans subjects voguing from Gran Vía to Plaza del Sol, by the black and indigenous knowledge that now sacrifices the hetero-colonial-civilizing project in the Metropolis’ Matadero [10].

In one of their most recent installations at the Sydney Biennale (2020), titled don't blame us for what happened, Ayllu explored the heterosexual colonial project and the legacy of said project in the political repression of gender and sexual practices in Abya Yala. Designed like Andean huacas [11], the installation rejected heteronormative discourse and articulated the struggle and survival of those who colonialism and coloniality have tried to erase for centuries. The installation was composed of four parts: “eat gold! insatiable white conquero”, “our gender are ancestral drifts”, “Pachakuti mood” and “Around the world: my body is a checkpoint/my body is a borderland.”

Throughout the installation, the collective narrated the historical violence against non-binary subjects; from dog attacks on indigenous sodomites in the sixteenth century to mass arrests of homosexuals in Mexico, Paraguay, and Ecuador in the twentieth century. Beyond representing the continuous and systemic violence to which the heteronormative discourse exposes the “abnormal”, the sexual dissident, don't blame us for what happened is an act of resistance, a collective voice that breaks with the imposed silence and says: “In 2020 we, Black and Indigenous sodomites, are still alive and with wounds we dance the pain away.” [12]

By giving voice to the stories of non-heteronormative subjects this installation affirms the political agency of nonbinary subjects while inscribing them into the present. Ayllu’s artistic work is thus centered on building an artistic-political practice that enunciates other conceptions of being that are deemed impossibilities under Euromodernity.

By Way of Conclusion:

The question that opens this reflection invites us to think and do otherwise, to imagine other models for understanding. The artistic-political work of the Colectivo Ayllu presents a possible answer to how we can get to that otherwise. By articulating its theoretical-artistic work in opposition to a modern/colonial/capitalist/patriarchal system, Ayllu advances an ecology of knowledge from the otherwise. Through its project of liberation for, which focuses on the construction of other ways of being, thinking and doing, the collective posits a decoloniality in praxis. It poses an epistemic and political project that emphasizes not simply the denial of coloniality but the existence and survival of other knowledges, temporalities, and ways of being. Through their artistic work, a collective practice of liberation for, Ayllu makes visible what Euromodernity seeks to erase and articulates other ways of being, thinking, knowing, and doing. That is to say, they think and do otherwise.

Notes

[1] An important line of decolonial thought is decolonial feminism. For more see: Tejiendo de otro modo: Feminismo, epistemología y apuestas decoloniales en Abya Yala, edited by Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso, Diana Gómez Correal, and Karina Ochoa Muñoz. Editorial Universidad del Cauca, 2014.

[2] Nelson Maldonado-Torres states: “The decolonial turn does not refer to a single theoretical school, but rather points to a family of diverse positions that share a view of coloniality as a fundamental problem in the modern (as well as postmodern and information) age, and of decolonization or decoloniality as a necessary task that remains unfinished” (2). See Nelson Maldonado-Torres. “Thinking through the Decolonial Turn: Post-continental Interventions in Theory, Philosophy, and Critique—An Introduction.” Transmodernity, 2011.

[3] In “Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina,” Aníbal Quijano proposes the concept of the “coloniality of power.” According to Quijano, the colonization of the Americas left behind a system of hierarchical relationships between white/dominant and non-white/dominated peoples.

[4] My own translation from the Spanish: “orden histórico-político-económico” (146). See Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso. “De por qué es necesario un feminismo descolonial: diferenciación, dominación co-constitutiva de la modernidad occidental y el fin de la política de identidad.” Solar, 12.1, 2016.

[5] Walsh argues that the decolonization processes must be articulated not as decolonization from but as decolonization for. She states: “And, on the other hand, the question is how this praxis interrupts and cracks the modern/colonial/ capitalist/heteropatriarchal matrices of power, and advances other ways of being, thinking, knowing, theorizing, analyzing, feeling, acting, and living for us all—the otherwise that is the decolonial for” (9-10). See Catherine Walsh. “Decoloniality in/as Praxis.” On Decoloniality. Duke UP, 2018.

[6] Gordon states: “There is always ‘too many’ members of a racially degraded group around, which makes them what the French call de trop (roughly, unnecessary, unwanted, or unsuitable)” (23). See Lewis R. Gordon. Freedom, Justice, and Decolonization. Routledge, 2021.

[7] My translation from the Spanish: “Grupo colaborativo de investigación y acción artístico-político formado por agentes migrantes, racializadas, disidentes sexuales y de género provenientes de las excolonias” Colectivo Ayllu. Ayllu. Matadero Madrid (2020).

[8] It should be noted that, although this essay focuses on the work of the Collective, its members separately have an important corpus of theoretical and artistic publications. For more on the theoretical work of Ayllu, see their books: No existe sexo sin racialización (2017), Devuélvannos el Oro: Cosmovisiones perversas y acciones anticoloniales (2018) No son 50, son 500 años de Resistencia: 10 años de migrantes transgresorxs (2019) and Sete mil rios nos comunicam (2021).

[9] The collective also has an important pedagogical program, Programa Orientado a Prácticas Subalternas (POPS), where they teach seminars centered on ancestral, indigenous Afro and trans epistemologies and ontologies.

[10] Lavapiés is an immigrant neighborhood in the center of Madrid; Gran Vía and Plaza del Sol are the two main squares in Madrid city center; and The Matadero, now an artistic space, was traditionally the slaughterhouse of the city.

[11] Inca sanctuaries or tombs.

[12] Colectivo Ayllu, “don’t blame us for what happened.” 22nd Biennale of Sydney (2020).

References

Gordon, Lewis R. Freedom, Justice, and Decolonization. Routledge, 2021.

Walsh, Catherine. “Decoloniality in/as Praxis.” On Decoloniality. Duke UP, 2018.

Dr. Vialcary Crisóstomo Tejada is an Assistant Professor of Spanish at the University of Rochester. She received her PhD from the University of Connecticut in Latin American and Caribbean Literatures and Cultures. Her areas of specialization include Afro-Caribbean Studies, Latinx Studies, Latin American Literature, Decolonial Feminism, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. She is currently working on her first book, titled Spaces of Resistance, in which she analyzes representations of Black and gender non-binary bodies in feminist Caribbean literature as contestations to hegemonic notions of race, gender, sexuality, and to the naturalizing effects of space endorsed by the State. The monograph dialogues with notions of cimarronaje (marronage) and proposes a relational and collective conception of identity. Her current research focuses on Black and feminist collectives in the Caribbean, Abya Yala and its diasporas. She is also the co-founder and co-editor-in-chief of Candela Review, a peer-review and open access Afro-Feminist journal.

![[Colectivo Ayllu, "don’t blame us for what happened" (2019-2020)]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5fc7fe3cba91e34ba34df9bf/1674734093886-DYEUBGQUSFNARTIUIL4O/unnamed.jpg)