Coloniality, Sexuality, and Rejection: From Frantz Fanon to Gloria Anzaldúa

By Alesandra Gutiérrez

Notions of rejection have unsurprisingly been put forward by several thinkers grappling with the weight of racial-colonialism. In this work, I am interested in tracing the manifestation of this affect across a multitude of spatiotemporal locations to investigate ways colonial subjects grapple with the weight of coloniality on emotions, relationships, and sexuality.

Nearly three-quarters of a century ago, Frantz Fanon provided a chilling account of what it meant to move through the world under the prescribed identity of the colonized Black subject (“la nègre”). Facing rejection from the white world, Fanon, like so many others, searches at first for solace: “I turn away from these prophets of doom and cling to my brothers, Negroes like myself. To my horror, they reject me” (Black Skin, White Masks, 70). Feelings of undesirability abound, as paradoxically hyper-sexualization results not only in fetishistic desires but also exclusion from normative society – in other words, rejection from one’s home culture and colonial culture alike.

In 1987, Gloria Anzaldúa wrote in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, that the notion of desirability is governed through the fear of rejection: “Fear of going home. And of not being taken in. We’re afraid of being abandoned by the mother, the culture, la Raza, for being unacceptable, faulty, damaged. Most of us unconsciously believe that if we reveal this unacceptable aspect of the self our mother/culture/race will totally reject us” (20). Anzaldúa wrote extensively on experiences of being rejected by white society, heterosexual society, patriarchal society, and the many other forms of dominant, normative society. Here, the fear associated with risking rejection from the home culture adds a new layer of nuance to desirability and acceptance, as is the case with Fanon.

There are certainly commonalities between the experiences of these two subjects, such as the general experience of living under the legacy of colonization and experiencing profound, acute racism. That said, one cannot ignore the obvious differences – geographical location, differing colonial experiences, gender, sexuality, and a plethora of other nuances regarding identity and social positionality. Nonetheless, both articulate a sense of rejection from normative society and from their own people. Both describe fear, horror, and a degree of self-blame.

Within these two vulnerable texts, both Fanon and Anzaldúa go on to discuss the notion of touch sexuality. Chapters Two and Three of Black Skin, White Masks are entirely dedicated to sexuality and relationships between people of color and the Black subject. In craving acceptance writ large, Fanon turns to love and touch: “Out of the blackest part of my soul … surges up this desire to be suddenly white. I want to be recognized not as Black, but as White … Who better than the white woman to bring this about? By loving me, she proves to me that I am worthy of white love. I am loved like a white man” (29). Of all things, Fanon acknowledges that his desire to step into the white sphere and obtain white status can only be made possible by relations with a white body. [1] What is so significant about touch, love, and desire to make this so?

Anzaldúa offers a different stance on the same concern: “For the lesbian of color, the ultimate rebellion she can make against her native culture is through her sexual behavior” (Borderlands, 31). Not by rejecting the church, not by disrespecting her elders, not by committing a crime against the law. No. These things are all encompassed by – collapsed onto – her sexual behavior. The fact that she identifies as queer or homosexual is not the true crime. Rather, her behavior, the way she engages her sexuality in touch, in love, and in gaze – this is the ultimate rebellion. I ask again, why this emphasis on sexuality?

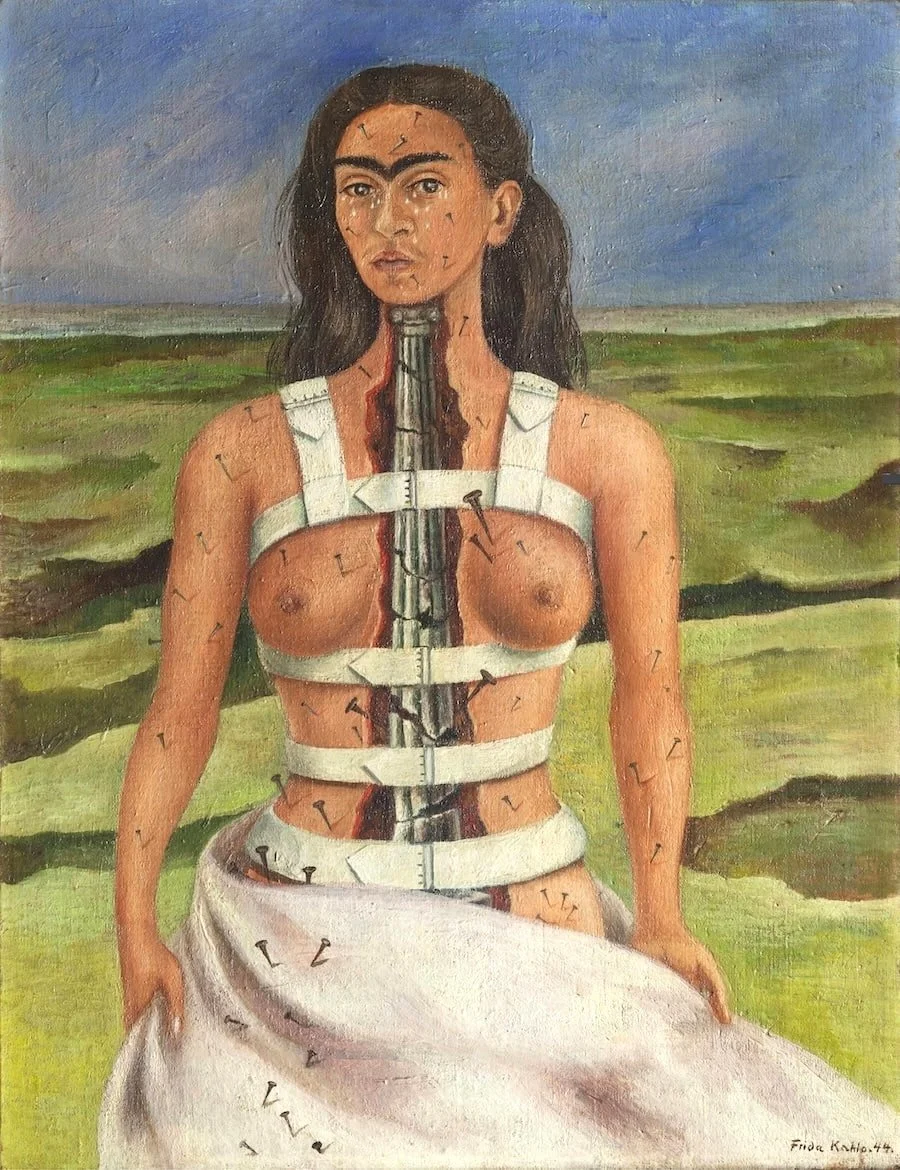

[Frida Kahlo, “The Broken Column,” 1944]

At the root of rejection, vastly different writers hold sexual relations and behavior as core factors. Through these texts that explore such deeply rooted emotions – Fanon’s self-deprecation, Anzaldúa’s unbelonging, the constant rejection, displacement, and sadness they both face – I find love and desire as a shared theme, shared concern. The impacts of racial, colonial structures on sexuality and relationships are by no means under-discussed. Fanon himself illustrates the experience of the male colonial subject becoming overdetermined by their sexuality and sexual organs: “[When] we let ourselves be carried away by the movement of images, no longer do we see the black man; we see a penis: the black man has been occulted. He has been turned into a penis. He is a penis” (117). While he may be focused on the lived experience of racialized men, many theorists discuss sexuality in terms of coloniality and vice versa. [2]

In “Coloniality and Gender,” María Lugones goes as far as to state that colonized women were animalized, “characterized along a gamut of sexual aggression and perversion” (52-53). There is a loss of humanity, a portrayal of some sexual Other. Yet, when seeking to understand this felt rejection, quite dissimilar subjects living in the legacy of colonialism turn to sexuality as some sort of answer or explanation.

In bridging this connection, I urge us to consider the ways love, touch, desire, sexuality, and relationships are touched, shaped, and perhaps wounded by racial colonial structures across lines of race, gender, and social geography. That is not to say that there are necessarily similarities in these two experiences, nor that we ought to set aside the impacts of differing racial, gendered, and geopolitical experiences. Rather, what I seek to point out is that when we look beyond these separations, we can find commonalities that can lead us to deepen our study of where we stand today in the legacy of colonialism which continues to entrench both hyper-sexualization and rejection.

Thus, I argue that only through a more complete analysis of past accounts of such experiences can we hope to grapple against these harmful norms that over-determine emotional and sexual experiences. As we continue to study sentiments of rejection, as we continue to develop the conversation of coloniality as it intersects with love and sexuality, let us consider how we can maintain necessary specifications and localizations without excessively severing shared experiences between demographics. Let us further our lines of questioning by considering why these experiences are shared.

Notes

[1] It is worth noting that Fanon problematizes this desire throughout the text, including in the latter parts of Chapter Three. I recommend viewing Chapter Eight for further reconfigurations of Blackness around touch, intimacy, and desire.

[2] For further reading, consider Carolyn Ureña. “Loving from Below: Of (De)colonial Love and Other Demons.” Hypatia 32:1 (2017): 86-102 and Sylvia Tamale. “Challenging the Coloniality of Sex, Gender, and Sexuality.” Intellectus: The African Journal of Philosophy 1:1 (2020): 57–79.

References

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 5th Edition. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books, 2022.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 2023.

Lugones, María. “The Coloniality of Gender.” In Feminisms in Movement: Theories and Practices from the Americas. Eds. Lívia De Souza Lima, Edith Otero Quezada, and Julia Roth. Bielefeld, Germany: Verlag, 2023: 35-58.

Alesandra Gutiérrez is a PhD student in Philosophy at Texas A&M University studying Latin American and Caribbean philosophy, social and political philosophy, and anti-colonial thought. Her current research is primarily focused on emotion and violence for gendered and/or racialized subjects, particularly in the context of Latin America and Latino communities. Her interdisciplinary research stems from psychology, sociology, and narrative. She serves as the Secretary of Graduate Outreach for the Caribbean Philosophical Association.