An Ode to the Domestics, the Minors of Apartheid, My Grandmother Among Them

By Zinhle ka’Nobuhlaluse

This essay is an ode to the domestics, the “minors,” the Others’ others’ other, the Black women of South Africa. [1] It is a dedication to my maternal grandmother, Sibongile Josephine, who was married off to the Mtshali family and born into a world that demanded her usefulness long before it imagined her freedom. Many elements of her life are unknown to me; some my mother shares in fragments, and others I have come to intuit through my work on Apartheid South Africa, and others from growing up its immediate afterlives.

What I know are the facts that survived bureaucracy: she was born on the 2nd of July 1942, but the Department of Home Affairs, in its habitual indifference to Black lives, recorded her birth year as 1943. Such errors were not mere clerical mistakes but symbolic erasures; reminders that under Apartheid, Blacks were fungible. [2] And yet, through the work of Black feminist and Africana philosophy, I have begun to recover her from that misfiled time.

[Anonymous, “Sibongile Josephine Mtshali on her Wedding Day,” 1960]

Working on Apartheid, its internal logics, and the “given” facts that structured everyday life has helped me understand myself, family, nation, and people. That said, there were some aspects of the system that were already familiar to me, having grown up in post-Apartheid South Africa. I knew that segregation was legalized in 1948, and that the Population Registration Act of 1950 codified racial hierarchies, declaring whites the pinnacle of humanity and everyone else subhuman. Even within that imposed subhumanity, there were gradations: Coloured and Indian people were granted more rights than Blacks. I also knew that access to education, health care, and citizenship was organized around the logic of white supremacy; anyone who was not white was structurally made to be without.

I was aware, too, of the major historical moments of resistance and brutality that define Apartheid in public memory: the 1956 Women’s March against the pass laws; the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre (when police killed Blacks who were protesting against the pass laws and the general conditions of unlivability); and the 1976 Soweto Uprising (where approximately 20,000 Black students were killed while protesting the imposition of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction under the Bantu Education Act).

This time period was also memorialized in texts such as Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country (1948) and Shaun Johnson’s The Native Commissioner (2006), which were part of my 12th-grade English curriculum. These texts offered a view of South Africa’s moral landscape, but always from a distance - from a framework that sympathized with Black suffering without quite inhabiting it. By the time I began my undergraduate education at the University of Johannesburg in 2012, I had already fallen into the rabbit hole of reading works by Black authors who had been excluded from my formal education. One such author was Steve Bantu Biko, whose collection of essays, published in I Write What I Like (1978), gave form to a consciousness I had felt but did not have the language for: the experience of living in a world that denies one’s humanity while depending on it.

Yet, I soon realized that many of the essays in I Write What I Like, although rich in historical detail, remained strikingly silent on the experiences of Black women. [3] It was only when I encountered Ellen Kuzwayo’s Call Me Woman (2016) and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s Part of My Soul Went With Him (1985) and 491 Days: Prisoner Number 1323/69 (2013) that I began to understand the full extent to which Apartheid was not only racialized but also profoundly gendered and classed. Naturally, as a philosopher, I sought out more autobiographical texts that write from and within the lived experiences of Black women, rather than about them. My search led me to Mamphela Ramphele’s A Life (1995), Caesarina Kona Makhoere’s No Child’s Play: Prison Under Apartheid (1988), Miriam Makeba’s Makeba: My Story (1988), Prodigal Daughters (2019) edited by Lauretta Ngcobo, and Phyllis Ntantala’s A Life’s Mosaic (1993), among others. Each book illuminated a facet of the Black woman’s condition under Apartheid that theory alone cannot reach. No English words are sufficient to capture what these texts did for me; they affirmed that autobiography, too, can be philosophy.

For example, Kuzwayo’s Call Me Woman (2016) taught me that Black women were considered minors by the regime; ‘Minors’ compared to their own sons” (275). Kuzwayo herself had to ask her son for permission to travel, as he was considered her guardian in the absence of her husband. In addition, reading No Child’s Play highlighted the systemic dehumanization of Black women and children within prisons. If a Black woman were with her child at the time of her arrest, the child would also be imprisoned. Yet, Makhoere notes that during her time at Kroonstad Prison, “not a single white woman had her own child in prison with her. Their kids got cared for outside, because it was thought that their children would be psychologically affected” (39). It should be noted that Makhoere, like other Black women authors, also wrote about their various acts of resistance to the regime, not just their subjection.

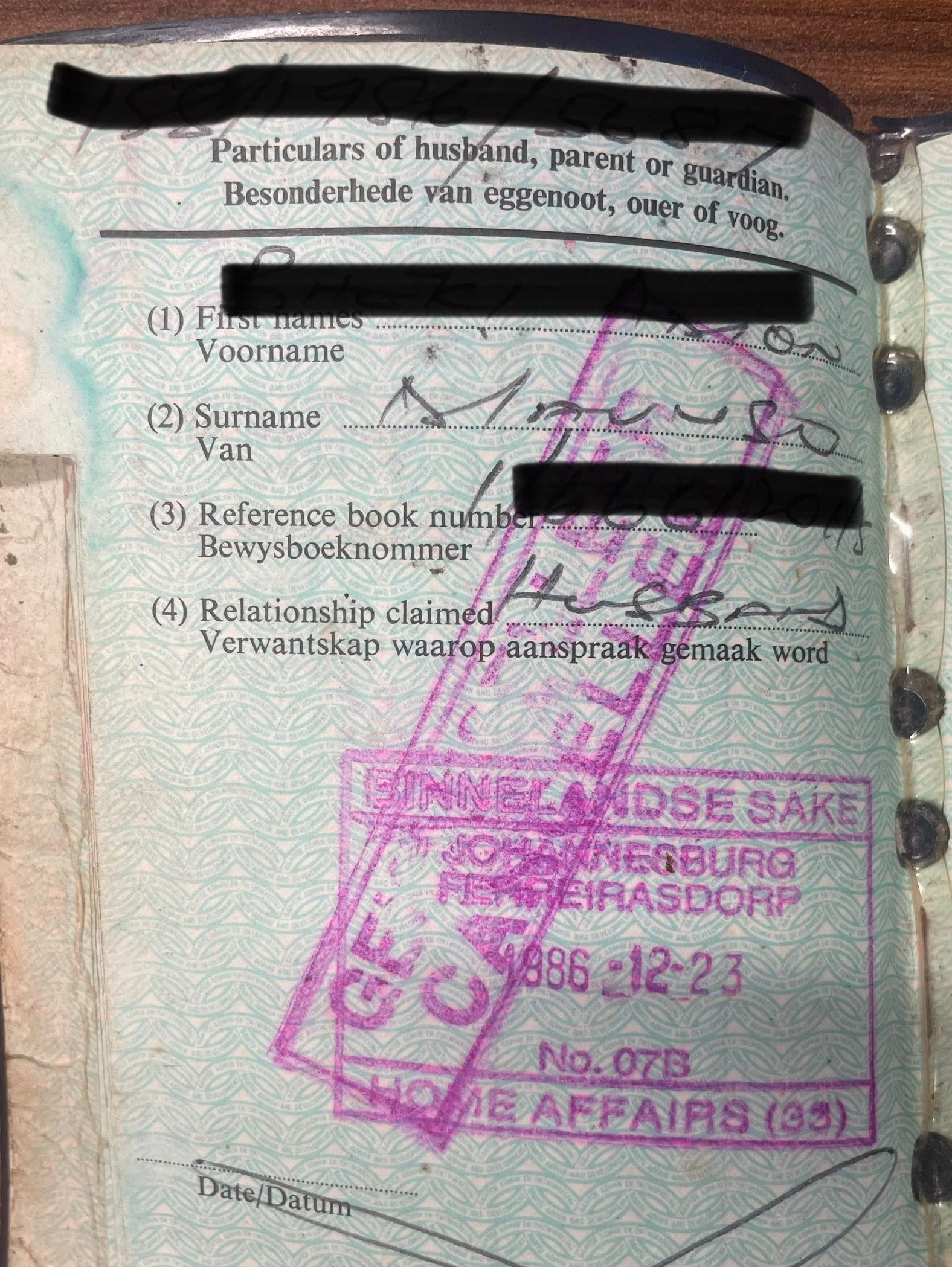

Redacted Reference/Passbook

I would like to thank my mum’s older sister, Thokozile Regina Mavuso, for giving me her reference book. Sometimes our archives are not the silent stacks of a library, bound in dust and catalog numbers, but the living ancestors who carry memory in their voices, gestures, and care.

Through reading these texts, I also gained empathy towards my mother, my grandmother, and all my kinfolk. I began to piece together– fabulate – a better understanding of my maternal line and how the regime’s machinery had ruptured it. In what ways, you may ask? [4] As my mother’s only daughter, I was always curious about her upbringing. I never understood why she wasn’t as close to her mother as we were. To this day, I speak to my mother daily; I am her keeper. However, between my mother and her mother, Jose, as we affectionately call her, a distance remains.

Importantly, my grandmother worked as a domestic worker during Apartheid as well as in its immediate aftermath. In South African colloquial speech, specifically in isiZulu, to work as a domestic is to work emakhishini - in the white woman’s kitchen. South African feminist scholar Gabeba Baderoon, in her essay “The Ghost in the House: Women, Race and Domesticity in South Africa” (2014), traces the lineage and specificity of this word. “Domestic,” she explains, is not only an adjective but a noun, "it means ‘servant,’ as in, she is the ‘domestic’” (175). The term itself is racially marked: in the South African imaginary, “the domestic” is always Black and always female. In this regard, being a ‘domestic’ is not merely an economic condition but a spatial one. Emakhishini were extensions of racism, spaces that structured proximity to whiteness while enforcing exclusion. In those confined domestic quarters, Black women lived within reach yet out of sight, indispensable yet unseen. [5]

While working emakhishi enabled Black women to earn money to support their families, the job required them to live on the properties of white families, and access to their own families depended on the whims of their employers. In the case of Jose, as with many other Black women, she would be granted only a single day of leave from work every other Sunday. As a result, my mother was denied the same tenderness her mother had given to her employers’ children. Visits were rare, expensive, and heavily regulated. One can then imagine how Black families were fractured and denied various forms of intimacy. It has been through working on and writing about Apartheid that I have come to understand the silences in my mother’s stories about her upbringing. Each sentence I write feels like a small act of translation, a way of hearing aspects of Apartheid that are missed when we focus only on its laws.

For instance, Jose was born and raised in a section of Soweto called White City. Established in the 1930-40s, White City was planned as a settlement for Black labourers who worked in the nearby metropolis of Johannesburg after being forcibly removed from their inner-city homes so the city could remain ‘clean’, ‘luminous’, and white. White City, as a name, thus speaks not of its residents but of a fantasy: a colonial dream of modernity and “compartmentalization” (3), to use Frantz Fanon’s description in The Wretched of the Earth, that was projected onto Black lives. White City, like many Black townships, suffered from deliberate neglect, lacking basic municipal services and surrounded by industrial buffer zones that reinforced both physical and symbolic separation from white neighborhoods. To call such a place White City was to perform a metaphysics of distance; to build a geography where whiteness named the ideal and Blackness bore its weight.

And yet, from this so-called White City, my grandmother emerged. A young girl, who would come to know the world through the absence of rights, rest, and recognition. Her name, labour, and being under Apartheid would be bound to whites and Black men’s ease. When she separated from her husband, the burden of child-rearing fell entirely on her shoulders, as it did for so many Black women of her generation. While I can theorize and fabulate the conditions of Black life in White City, I find myself asking what that little girl might have dreamt for herself. What songs did she hum when no one listened? What did she make of the word “freedom?”

In other words, what is her story apart from being deemed a minor, domestic, and so-called non-white qua non-human by the regime, even as it was Black women’s labour as emakhishi that gave white women newfound freedoms away from the domestic work. Black women’s reproductive labour sustained both white families and, indirectly, the social possibility of Black men’s rest. The “ease” that eluded her was made possible for others through her exhaustion, endurance, and unacknowledged care. Even though my grandmother is still alive, I cannot ask her these things, not fully; distance and time conspire to keep us apart. She is in South Africa. And I am in the United States.

When I think of my grandmother’s job emakhishini, as the ‘domestic,’ I am reminded of South African artist Mary Sibande’s sculpture, “They Don’t Make Them Like They Used To” (2008). In that work, a Black woman named Sophie stands in an exaggerated domestic uniform: a deep blue dress, crisp white apron, and headscarf tied with habitual precision. Her attire is both burden and inheritance; it recalls the enforced roles Black women under Apartheid endured, yet it also quietly transforms that memory. The dress, too grand for the narrow confines of servitude, spills into excess and refuses to be contained. In that refusal, Sibande’s work accomplishes what Black feminist philosophy insists upon: turning what was once a mark of subjection into a space of becoming. Indeed, Sophie stands boldly, knitting what appears to be a piece of Superman’s uniform. The ‘S’ is not merely printed or worn on, but carefully stitched with much care, repetition, and time.

[Mary Sibande, “They Don't Make Them Like They Used To,” 2008]

While reminiscent of Superman, the ‘S’ also evokes Sophie, Sibande’s stand-in for generations of Black women whose labour sustained others’ ease, not forgetting the many white men (the beneficiaries, architects of Apartheid) who were nursed by the domestics. Sophie thus transforms a symbol of power and masculine heroism into something domestic, feminine, and tangible. My reading is set against the backdrop of the various meanings behind Superman’s ‘S’, which stands as an initial, a family insignia, and a cosmic emblem of hope. The ‘S’ is the crest of the House of El, a mark of noble lineage, signifying both belonging and distinction. In addition, the ‘S’ also functions as the Kryptonian symbol of optimism, a sign of redemption and moral certainty. [6] However, when applied to the context of the ‘domestic’, these meanings are both inherited and subverted. The initial becomes personal rather than Universal (perhaps Sophie, not Superman), marking an individual whose life was defined not by superhuman capacity but by the everyday endurance of systemic violence.

In Sophie, I see the hands of my grandmother, wrapped in resilience. The sculpture embodies the contradiction of visibility and erasure, labour and longing, Blackwomanhood as both spectacle and silence. Sibande, for me, conjures an image that demands us to reconsider the metaphysics of the “domestic.” Her artwork reminds me that every seam, every fold of fabric, is a text; that the uniform of servitude, when viewed through Black feminist eyes, becomes a theory of freedom still in the making.

So, this is my dedication, my inheritance. I write for Sibongile Josephine and for every Black woman who made the world livable, even when the planet deemed them non-human, alien, non-citizen.

Notes

[1] During Apartheid, Black women were legally and socially classified as minors, not by age, but by status. They were not allowed to own property, or sign contracts without the approval of their legal guardian which for married women was their husband and unmarried women their father.

[2] My use of the term draws from Saidiya Hartman who develops the term to describe how the transatlantic slavery and its afterlives rendered Black people as commodity, exchange and violation. See Saidiya Hartman. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997: 21–25.

[3] There is long research by South African Black Feminist thinkers who highlight the sexism in the Black Consciousness Movement. For more, see Mamphela Ramphele. “The Dynamics of Gender Within Black Consciousness Organisations: A Personal View.” In Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko and Black Consciousness. Eds. N. Barney Pityana, Mamphela Ramphele, Malusi Mpumlwana, and Lindy Wilson. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 1991, as well as Pumla Dineo Gqola. “Contradictory locations: Blackwomen and the discourse of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) in South Africa.” Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 2:1 (2001): 130–152.

[4] Hartman describes critical fabulation as a methodological approach that integrates archival research with speculative storytelling to confront the silences and omissions that shape historical records as they relate to the lives of enslaved Black women. For more information, see Saidiya Hartman. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12:2 (2008): 11–13.

[5] To understand the intersectional dynamics of domestic servitude and gendered exploitation, see Jacklyn Cock. “Disposable nannies: Domestic servants in the political economy of South Africa.” Review of African Political Economy 8:21 (1981): 63-83.

[6] Many thanks to Dana Miranda for inviting me to reflect more on the Superman imagery. I look forward to developing this essay into a longer article.

References

Baderoon, Gabeba. “The Ghost in the House: Women, Race and Domesticity in South Africa.” In Desire Lines: Space, Memory and Identity in the Post-Apartheid City. Eds. Nicky Falkof and Louise Bethlehem. New York: Routledge, 2014: 170-186.

Biko, Steve. I Write What I Like: Selected Writings. Ed. Aelred Stubbs. London: Heinemann, 1978.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Johnson, Shaun. The Native Commissioner. Johannesburg: Penguin Books, 2006.

Kuzwayo, Ellen. Call Me Woman. Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2016.

Madikizela-Mandela, Winnie. Part of My Soul Went with Him. New York: W.W. Norton, 1985.

Madikizela-Mandela, Winnie. 491 Days: Prisoner Number 1323/69. Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2013.

Makeba, Miriam. Makeba: My Story. New York: Dutton, 1988.

Makhoere, Caesarina Kona. No Child’s Play: Prison Under Apartheid. London: The Women’s Press, 1988.

Ngcobo, Lauretta, Ed. Prodigal Daughters: Stories of South African Women in Exile. Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2019.

Ntantala, Phyllis. A Life’s Mosaic: The Autobiography of Phyllis Ntantala. New York: Feminist Press, 1993.

Paton, Alan. Cry, the Beloved Country. London: Jonathan Cape, 1948.

Ramphele, Mamphela. A Life. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 1995.

Zinhle ka’Nobuhlaluse is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at Southwestern University and is affiliated with the SARChI Chair in African Feminist Imagination at Nelson Mandela University. Her work is situated at the intersection of critical philosophy of race, autobiography, and feminist philosophy. Zinhle has published in various academic journals, including Critical Philosophy of Race and Feminist Formations, and has written several public-facing essays published in Africa Is A Country and the APA Blog of Philosophy. They also serve as coordinator and moderator for the African Feminist Initiative’s virtual dialogues at Penn State.