Philosophies of the Trail

By A. Vine

On January 12, 1935, Adolphus Theodore, a 24-year-old Black Costa Rican, was arrested by Panama Canal Zone police. They charged him with vagrancy for being on a pier in Balboa, a port on the Pacific side of the Zone, without “legitimate business or visible means of support.” In addition, the arresting officer noted that Theodore had been carrying a pound of marijuana for sale. This may seem unremarkable, but at the time, neither the possession, sale, nor cultivation of cannabis was illegal in the Canal Zone.

In fact, U.S. colonial authorities had conducted three separate studies of cannabis in 1925, 1928, and 1932. Each time they concluded that marijuana was not causing crime, violence, or addiction, and declined to prohibit its use, cultivation, or sale by civilians. The U.S. did not publish the first two studies, but the third one, entitled “Mariajuana Smoking in Panama,” detailed the history of all three in a 1933 article in Military Surgeon. The committee of military doctors that ran the study upheld a cannabis ban for soldiers in the Canal Zone but recommended no change for civilian policy.

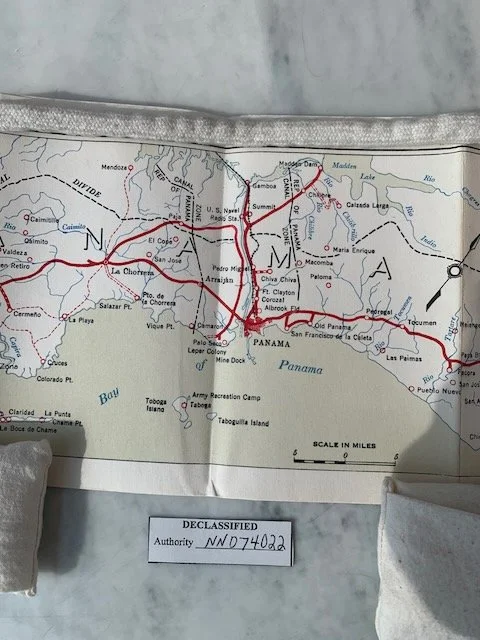

The undertaking of three studies in eight years signals that the Canal Zone was where thousands of U.S. soldiers had their early encounters with smoking marijuana, and the place where most of it was grown was an Afro-Caribbean village called Chiva Chiva (also Chiva-Chiva, Chivo Chivo and, rarely, Cheevo Cheevo). Time and again, in military reports and newspapers, the village was identified as the main source of cannabis in Panama and the Canal Zone, with the related Chiva Chiva Trail as its primary market.

To understand the marketplace in Panama, especially the one for marijuana, one must first make sense of the larger segregated economic landscape produced by the Silver and Gold payrolls—racially-coded payment categories employed by the U.S. in the Canal Zone. From the start of constructing the “inter-oceanic” railroad—that preceded the Canal— workers were imported from around the world, many from across the Caribbean (with most from Barbados and Jamaica). 5,000 West Indians were lured in the mid-1850s by railroad jobs, followed by 50,000 who came to work on the French canal project in the 1880s.

Finally, an estimated 150,000 workers showed up for the U.S. project between 1904 and the Canal’s opening in 1914. They came to a territory upon which the U.S. imposed a crude Jim Crow style segregation. The Gold class included only white U.S. citizens, while the Silver class referred to everyone else. Silver employees not only earned a quarter of their Gold counterparts; their status also demarcated their housing, healthcare, education, and shopping opportunities—in other words, every aspect of segregated life.

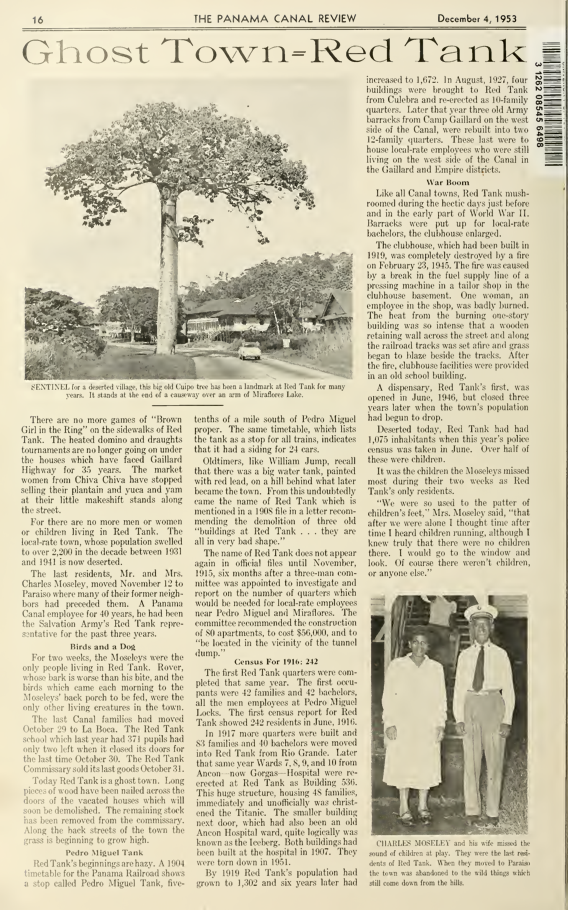

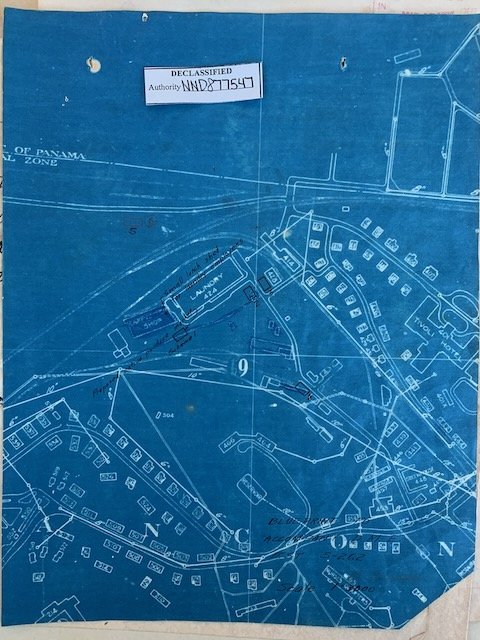

Chiva Chiva was a critical response to this discrimination as Black people could live in the area with a modicum of privacy. On land leased from the Canal Zone, they could determine their own housing and raise their own crops. The latter offered potential liberation from the Silver and Gold system, or a more immediate supplement to their meager earnings—provided that they could market their harvest. The Chiva Chiva Trail itself was only wide enough for a car, but the village was close enough to reach by foot. First, one would pass a Silver Town called Red Tank, with long blocks of multi-family housing, and then Fort Clayton.

At the time, Chiva Chiva was known as a source of fresh farm goods, including marijuana. Where the trail met Gaillard Highway, a fresh produce market served workers returning to Red Tank and, occasionally, soldiers looking for items they couldn’t find in the tax-free commissary.

[The Panama Canal Review, “Ghost Town = Red Tank,” December 4, 1953]

On this Trail, the predominantly white U.S. soldiers who guarded the Canal would buy and experiment with marijuana. They sometimes used the Trail and Gaillard Highway on their way to occupy Panama City to quell dissent against the prevailing socio-economic conditions. Importantly, economic conditions were oppressive for working people throughout the U.S. occupation of the Canal Zone. Wages were low, rents were high, and, after the Canal opened in August 1914, jobs were scarce. The ensuing economic depression made everything worse. The criminalizing of Theodore’s drug peddling on the pier can therefore be understood as part of U.S. efforts to monopolize control of Afro-Caribbean workers and spaces of exchange around the Panama Canal.

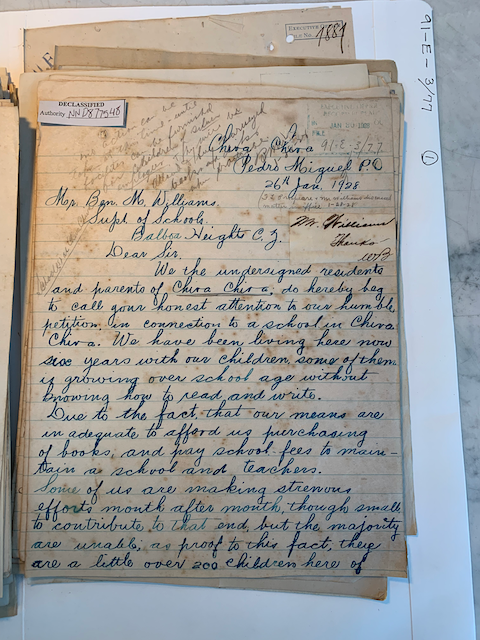

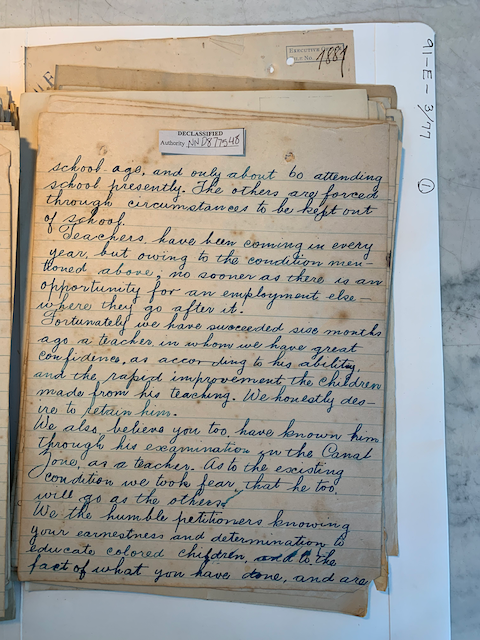

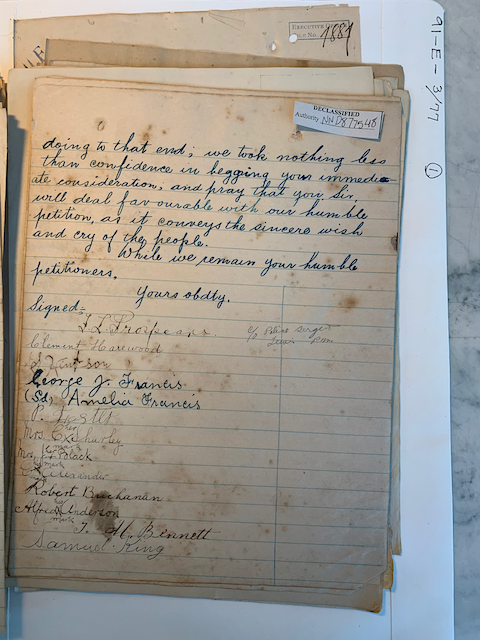

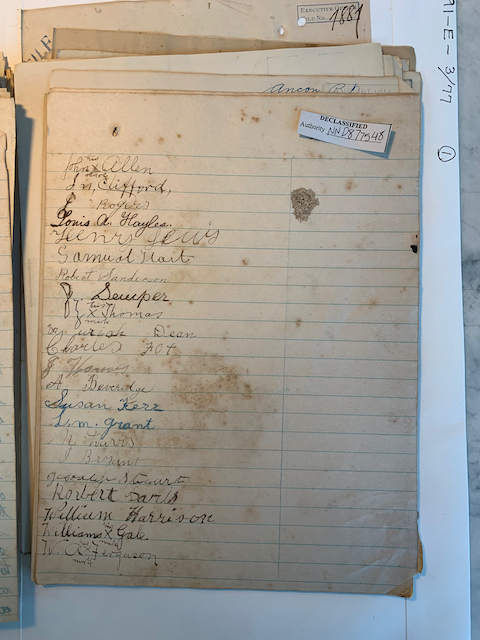

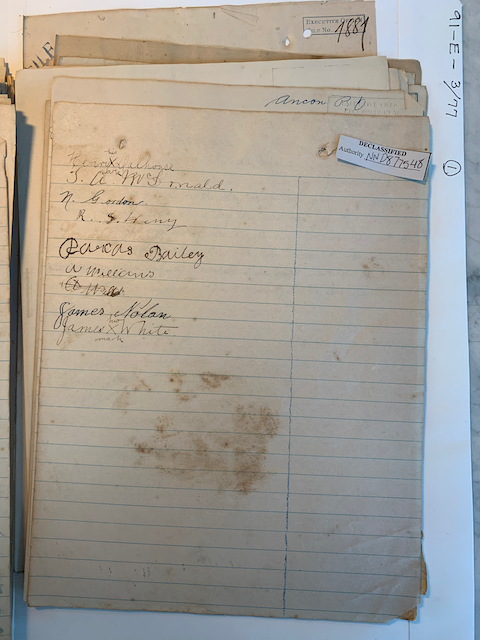

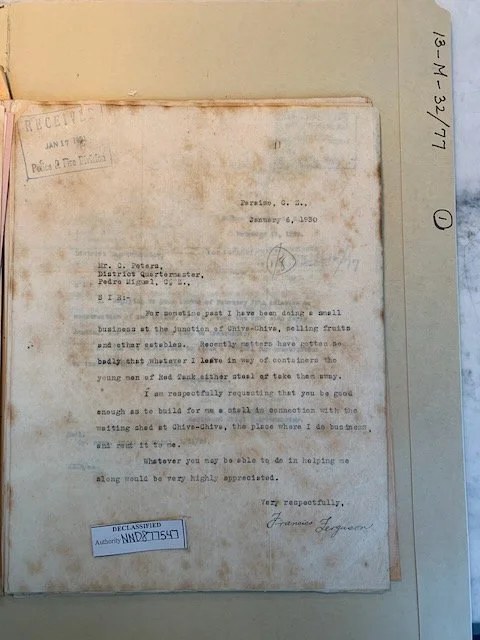

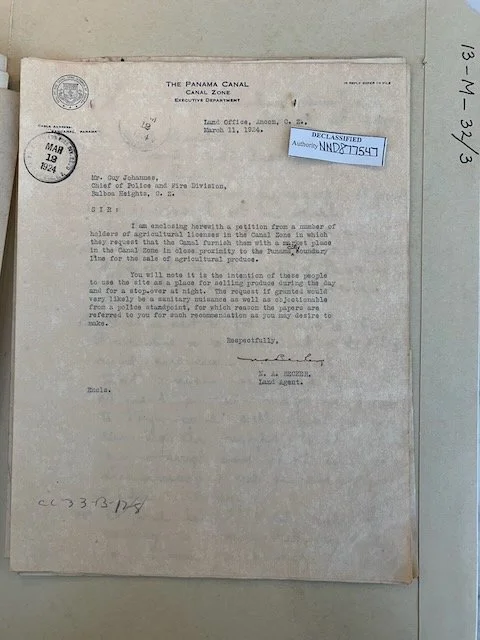

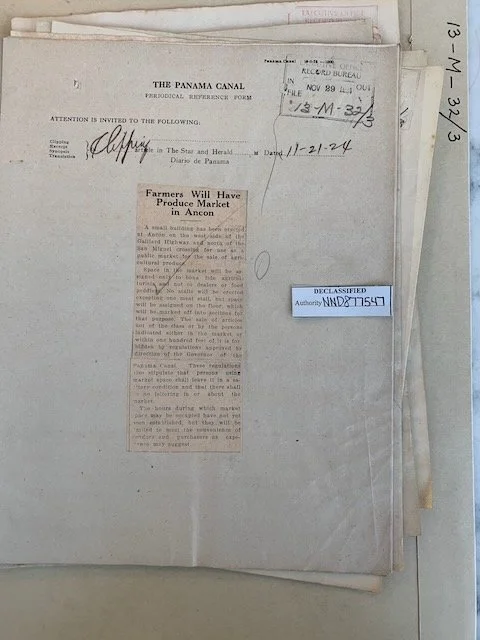

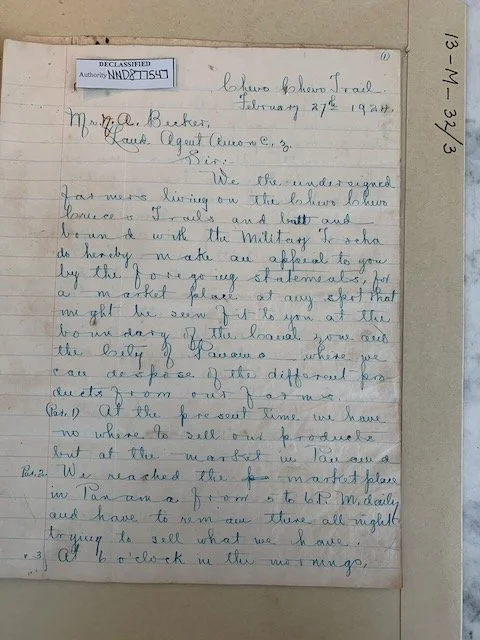

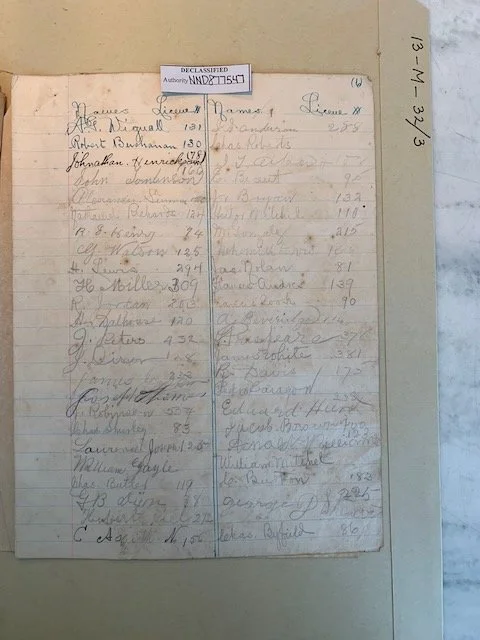

In its aftermath, three requests were submitted to U.S. authorities. In 1924, the farmers of Chiva Chiva sought the construction of a new market at the border of the Canal Zone and the Republic of Panama; in 1928, the people of the village asked for a school; and, in 1930, a 41 year-old Black Jamaican woman named Francies Ferguson requested a lockable stall, which she offered to rent, at the entrance to the Chiva Chiva Trail. I encountered these requests, along with Theodore’s arrest record, in the National Archives and Records Administration II (NARA II) in College Park, MD, in Record Group 185, which contains files from the civilian administration of the Canal Zone between 1914 and 1950. [1] In what follows, I reflect on the three requests because together they clearly express the shared wishes of the farmers of Chiva Chiva, and, I argue, suggest a philosophy of the Trail that could better inform conceptions of reparative cannabis policy. [2]

A Market on the Border

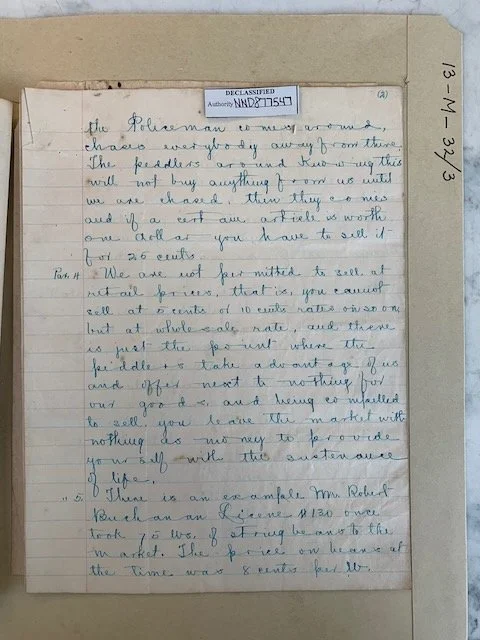

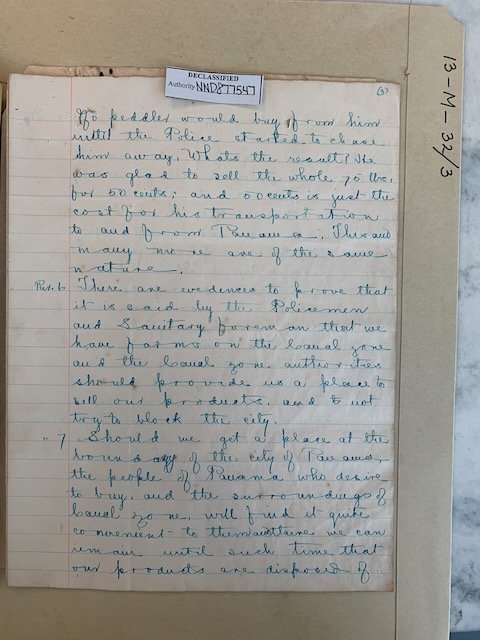

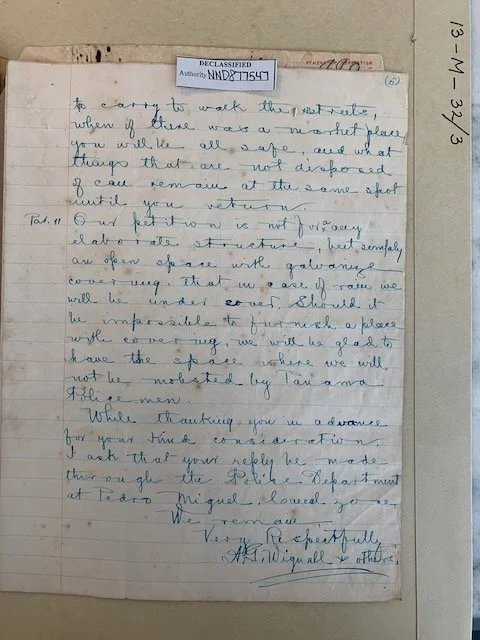

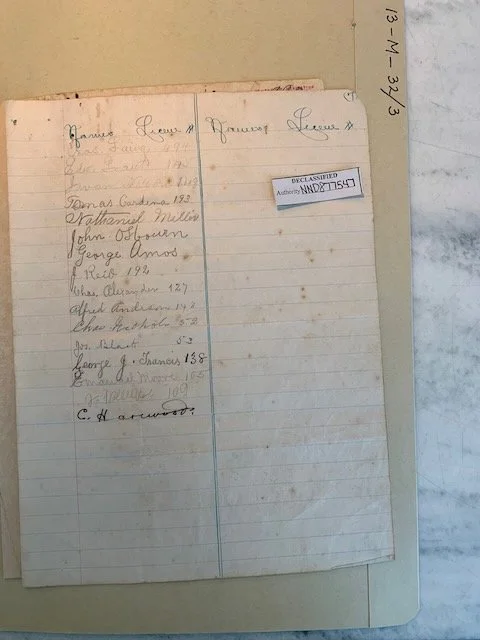

The first request was a letter, handwritten in 1924, and signed by 64 people. It asked for a market structure to be built on the border between the Canal Zone and the City of Panama. The lead author, A.G. Wignall, explained the predicament of farmers living on what he called the “Chevo Chevo Cruces Trail… bound with the Military Trocha” (also meaning path or trail). Chiva Chiva farmers were “not permitted to sell at retail prices” because they could not occupy the Panama City market during the daytime. Only able to enter the City at night, workers would remain in the market trying to sell their remaining produce at a steep discount before getting chased out in the morning by Panamanian police. Yet, at that hour, the only buyers of their discounted goods were “peddlers.”

To illustrate this issue, Wignall offered the example of Robert Buchanan who took 75 pounds of green beans to market. He was forced to sell them for $.08 a pound, rather than the $.80 they merited. This legal restriction reveals substantial state intervention on the part of the Panamanian police, which reduced farmers’ profits, lowered consumer prices, and generated an urban peddler class.

The 1924 request was a plea to be liberated from that intervention by the Panamanian police. The farmers asked only for “an open space with galvanize (sic) covering, that in case of rain we will be under cover.” They hoped, in this place, they would “not be molested by Panama policemen.” When the request was granted, a market was built between Chiva Chiva and Panama City, on the side of Gaillard Highway near the Canal Zone’s border with the Republic of Panama.

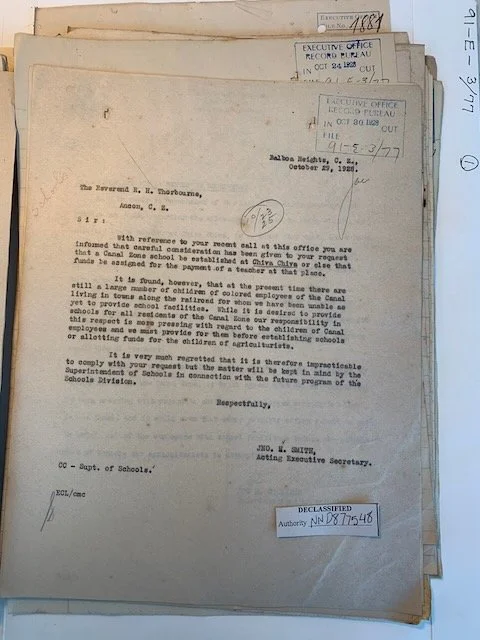

A Secondhand Schoolhouse

In 1928, 43 people collectively signed the petition for a school in Chiva Chiva. The petitioners, largely women, indicated that they had been living there for six years. Roger Buchanan, the aforementioned green bean farmer, signed this petition as well. Their letter stated that they had been trying to raise money to pay a teacher themselves, but their “means [were] inadequate to afford” books and keep a teacher employed. They noted: “Some of us are making strenuous efforts month after month, though small to contribute to that, but the majority are unable.”

Initially denied, the Canal Zone authorities explained that there were already hundreds of children in Silver towns without access to school, and that the Canal Zone government were obligated to address the needs of Canal Zone employees’ children before providing education for “agriculturists.” In this sense, the community was punished for its attempt to live outside the Silver and Gold system. By 1932, however, the Canal Zone government caved to the pressure that began with the letter and built a school in Chiva Chiva, with one teacher assigned to provide instruction.

The Waiting Shed

The third request was submitted by Francies Ferguson alone, in a simple typewritten letter punctuated by the elegance of her cursive signature. While the letter is dated January 6, 1930, it appears that she made the common January mistake of writing the previous year in place of the new one, which would have been 1931. In her request, Ferguson asked that a stall be constructed for her to sell “fruits and other eatables” in what she referred to as a “waiting shed” at the entrance to the Chiva Chiva Trail. Her demand was prompted by “young men from Red Tank” who had been stealing products she left in the unlocked shed.

During this time, the Great Depression had just begun, and unemployment was rising. The Black population of Panama, both in the Republic and the Canal Zone, came under increasing pressure. In internal Canal Zone office correspondence about the request, staffers wrote that Ferguson sold “food stuff only and has never given the department any trouble.” The implication was that she was not selling rum or marijuana; alcohol was, at the time, prohibited in the Canal Zone while cannabis was still legal and consumed as food and medicine. As Theodore’s arrest demonstrates, however, cannabis was already stigmatized. Cannabis was used most commonly by Afro-Caribbean residents (“especially the women”) as a tea and anti-malarial. While Ferguson’s involvement in the cannabis trade is uncertain, it was certainly sold around her stall, if not in it. Regardless, her request for a locked stall was ultimately granted. The protective area was built, and she was charged $2.00 per month for rent. State intervention thus appears in the form of protection for a farmers’ market.

All three requests, and some related documents, are included in the above image gallery. Many contain a “Declassified” number because, in the 1920s and 30s, both the U.S. general that oversaw the Canal Zone forts and the civilian governor that ran most everything else in parallel reported to the Secretary of War of the U.S. Department of War. Files related to their operations, especially those pertaining to race and labor issues, were once classified. Now declassified, they are stored at NARA II, College Park.

However, in 1935, Canal Zone authorities secretly banned cannabis cultivation. They informed Chiva Chiva farmers verbally so as not to alert the press, but, in 1938, the U.S. colonial governor banned it publicly. The penalty was eviction and, ultimately, deportation from the Zone. By 1953, the town of Red Tank had closed, and the Chiva Chiva market did as well. These actions were all part of the long U.S. depopulation campaign to push Afro-Caribbean communities out of the Zone. With the departure of U.S. troops in 1999, Fort Clayton shut down as well. It has since been redeveloped as Ciudad del Saber, or the City of Knowledge, with a restyled campus that hosts non-profit and academic programming aimed at incubating start-ups and entrepreneurs.

Cannabis laws have been changing again too. In the U.S., this has happened state by state, whereas Panama, as a country, legalized medical cannabis in 2021. Legal scholars Jasmin Mize, Garrett Halydier, and Kojo Koram have conceived of reparative cannabis policies that seek the redress of the consequences of cannabis prohibition, and some states and cities in the U.S. have begun implementing different iterations of them. [3] These often involve clearing people’s criminal records, allocating tax revenue to communities that have been disproportionately affected by cannabis arrests, and prioritizing access to licenses to operate in the newly developing cannabis industry for members of these communities.

Such market-focused programs, known as social equity programs, have largely emphasized retail (dispensary) licenses within a taxed-and-regulated system of corporate entities, even though these are known inevitably to spur illicit competition to supply consumers and patients with untaxed marijuana. [4] In particular, Koram has noted how cannabis legalization can reinforce the racialized inequalities of the Euromodern world. This can be seen in the limitations of reparative programs, which tend to be funded through regressive taxes on cannabis consumers, and which ignore small farmers in favor of corporations.

Few scholars have looked to the characteristics of the pre-prohibition Afro-Caribbean market for solutions. Yet I argue that the Chiva Chiva farmers’ desire for an unpoliced, but protected, marketplace offers a possible method of repair: an untaxed farmers market. This market is one where growers not only had the liberty to sell, but one in which the state provided “stalls” and protection. Could re-implementing that aspect of the pre-prohibition landscape, in which cannabis can be sold directly to consumers alongside other produce, constitute a form of economic redress to both farmer and consumer?

Taxing cannabis institutes a regressive tax on the very consumers that were, and still are, among the criminalized. So far, states and municipalities in the U.S., as well as nations that have legalized recreational cannabis like Canada and Uruguay, have used this tax revenue for administration of cannabis regulatory system, as well as reparative efforts, education, law enforcement, consumer education campaigns, and, most of all, for their “general funds.” These are the central pools of money in public budgets that typically funded the criminalization of cannabis in the first place. True repair would include diverting money from such general funds to repair the breach between farmer and consumer created by prohibition.

Within this framework, the arrest of Adolphus Theodore can be read as representative of the thousands—if not millions—of people whose charges did not reflect that they were, in essence, criminalized for cannabis. Selling weed was not illegal in Panama when Theodore was arrested, so what exactly was he charged for? In my estimation, he was charged with disrupting the racial order, in which the U.S. wanted to monopolize control over the market—namely, what goods could circulate, how they could be exchanged, and where that exchange would happen. The issue was not really with possession or distribution of cannabis, but who was doing it and under what circumstances.

This historical record also raises more complex questions about the sufficiency of reparative measures like record clearance, access to cannabis business licenses, and vague notions of community reinvestment. Record clearance, especially, is essential, but the Chiva Chiva letters suggest that construction of independent, community-based schools and open access to the agricultural marketplace, not simply for cannabis, are also valuable and necessary. [5] Valuable because the petitions reveal their deep meaning to the community and necessary because these were services not originally provided or once provided were then erased.

As scholars and policymakers continue the process of theorizing and building legal cannabis markets, we should continue to learn from the lessons of the Chiva Chiva Trail. Consider the following: Should a farmer’s ability to access the market, and set their own prices, be considered a right or, at least, a reparative necessity in and of itself? Should consumers’ and patients’ rights to affordable cannabis medicine be honored? How can “repair” be delivered to individuals and communities? How can regulated cannabis markets that do not lead to illicit, untaxed, and therefore criminalized, markets be created?

With President Trump’s renewed threats to seize the Canal, deployment of U.S. gunships to the Caribbean, and subsequent kidnapping of Venezuelan President Maduro and his wife, allegedly because of drug trafficking, the cycle of imperial violence in and around Panama has returned. As such, the answers to all our questions may not exist in the City of Knowledge; but some answers may remain just outside its walls, if we are willing to look.

Notes

[1] Box 344 File 13-M-32/77 holds the market-related letters, Box 580, File 91-E-3/77 contains the petition for a school, and Box 2332 includes file 94-A-103, the colonial administration’s marijuana file, in which Theodore’s arrest is memorialized.

[2] There is a robust literature on race, labor, gender, and culture in the Canal Zone, including, but not limited to, books on the efforts of Afro-Caribbean people in Panama to create communities and worlds (see Kaysha Corinealdi. Panama in Black: Afro-Caribbean World Making in the Twentieth Century. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022.), their letters and lives (see Julie Greene. Box 25: Archival Secrets, Caribbean Workers, and the Panama Canal. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2025.), the heretofore overlooked vending work of Afro-Caribbean women in local markets in the Zone (see Joan Flores-Villalobos. The Silver Women: How Black Women’s Labor Made the Panama Canal. Politics and Culture in Modern America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023), contrasted with the Canal Zone towns erased by U.S. authorities in their early depopulation campaigns (see Marixa Lasso. Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019), and the many borderlines, literal and figurative, that intersected the Zone (see Michael E. Donoghue. Borderland on the Isthmus: Race, Culture, and the Struggle for the Canal Zone. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014). Needless to say, without these scholars, this work would not exist.

[3] For more information on cannabis legalization and reparations, see Jasmin Mize. “Reefer Reparations.” Social Justice & Equity Law Journal 3:2 (2020): 1–35; Garrett Halydier. “We(Ed) the People of Cannabis, in Order to Form a More Equitable Industry: A Theory for Imagining New Social Equity Approaches to Cannabis Regulation.” University of Massachusetts Law Review 19:2 (2024): 1-113; and Kojo Koram. “The Legalization of Cannabis and the Question of Reparations.” Journal of International Economic Law 25:2 (2022): 294–311.

[4] For more information on social equity programs and cannabis, see Y. Tony Yang, Carla J. Berg, and Scott Burris. “Cannabis Equity Initiatives: Progress, Problems, and Potentials.” American Journal of Public Health 113:5 (2023): 487–89.

[5] From the U.S. point of view, Matthew Lassiter’s recent book, The Suburban Crisis, demonstrates that the system of drug diversion courts in the U.S. was built to handle white people’s drug cases; in contrast to the standard criminal courts chronicled in The New Jim Crow and countless other studies of the mass-incarceration complex constructed for Black, Indigenous, and other non-white groups. This dual track process finds an antecedent in the Silver and Gold system from the Canal Zone. See Matthew D. Lassiter. The Suburban Crisis: White America and the War on Drugs. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023.

References

Hetland, Gabriel. “Murder in the Caribbean.” NLR/Sidecar. October 16, 2025.

Phillips, Tom, Patricia Torres, and William Christou. “US has captured Venezuela's President Maduro and wife, says Trump.” The Guardian. January 3, 2026.

Siler, J.F., W.L Sheep, L.B. Bates, G.F. Clark, G.W. Cook, and W.A. Smith. “Mariajuana Smoking in Panama.” The Military Surgeon : Journal of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States 73:5 (1933): 269–280.

Waldenberg, Samantha and Michael Rios. “Trump reiterates threat to retake Panama Canal ‘or something very powerful’ will happen.” CNN. February 2, 2025.

Cover Photo Credit: Ney Coto Pinzon, “Raices,” 1993.

A. Vine is a writer, researcher, producer, and Master’s student at the University of Connecticut in the Intersectional Indigeneity, Race, Ethnicity, and Politics (IIREP) program. He has worked in the overlapping worlds of advocacy, media, and politics since 2008, with an emphasis on criminal justice reform, drug policy reform, and racial justice. He has organized national record clearance events, coordinated youth-led protests in Los Angeles, and produced media for non-profits and progressive campaigns. His writing has previously appeared in outlets such as Zócalo Public Square, Inquest, and Yes Plz Weekly.