Caribbean Thought from Ethnographic Enclosure

By Sarah Bruno

Redact

Re-dact: /rә’fak(t)/

To censure or obscure.

Since the onset of colonization, the Caribbean has been the locus of a conquistadorian ocular. What exists in the wake of that extractivist legacy is a culture of imperial gentrification driven by capitalistic dependence on tourism. [1] As an Afro-Puerto Rican anthropologist who uses Afro-sonic expressive culture as a site and method to anticipate, critique, and imagine beyond empire, the paradoxical experience of hypervisibility and weathered invisibility is one I know all too well. [2] In this short piece, I concern myself with the disciplining of the Caribbean as a field of study and how that lies in tension with Caribbean thought. I draw on my background as a poet and scholar invested in Black studies to perform a very brief orthographic redaction exercise to trouble the notions of erasure, opacity, and enclosure and manifest the tension between Caribbean area studies and Afro-Caribbean ontological theorization.

In Reproducing Empire, Laura Briggs names Puerto Rico as having “optimal” conditions for birth control developers to test their new procedures and hormonal contraceptives. In this way, the islands became the perfect laboratory–one filled with controlled populations in a contained geographic locale. In fact, the medical industry gathered these ideas via governmental reports and championed social scientists who accessed the region for their own purposes. Case in point: anthropologist Oscar Lewis, who wrote La Vida in 1965 based on research done in the 1950s, developing the framework for a “culture of poverty.” The culture of poverty model was brought out of Lewis’ ethnographic research on Puerto Ricans and Mexicans. This model was used to exacerbate the liminal positioning of Puerto Ricans within the United States, as well as frame Jamaicans via the narrative of a “culture of violence,” contributing to what Césaire called the thingification of colonial subjects. Within the Western academy, the Caribbean was seen, but it was not recognized.

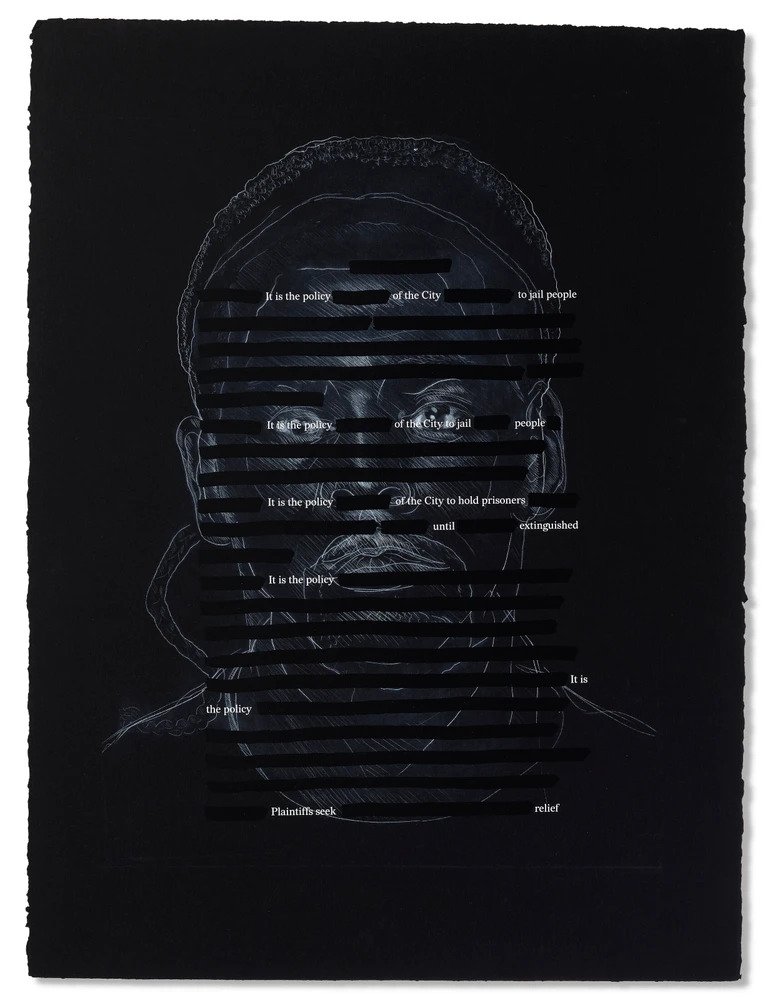

[Titus Kaphar, Untitled (Redaction), 2019]

In Dear Science, Katherine McKittrick discusses the aesthetics of redaction as an Afro-diasporic method and right to opacity. Here, I am drawing on redactive methods to make visible and plain the dangers of area studies. The redactive aesthetic within Black studies is reminiscent of erasure poems, however, I want to refrain from making a violent poetic beautiful. Violent poetry already permeates scholarship. There is no need to insert a close reading to make violence within the margins of those pages digestible. Instead, by making visible how loud and wrong white supremacy sits in texts, I align myself with the erased. The subjects of those sentences that were assumed about, I recognize them. I recognize the practice of opacity throughout the pages of La Vida and in early assessments of nations throughout the Caribbean. However, I also recognize the design for living in the redaction, the need for opacity, and the right to defend one’s way of life through intentional misunderstanding.

Prescriptive ethnographic representations of Afro-Caribbeans who live in the wake of the plantation often obscure their design for living. The word “redact” is derived from the Latin redigere, meaning to “bring back.” Caribbean thought, and for that matter Black thought, is a redirection that brings back focus on the methods of life and livingness within the piercing discourses that can term theirs as a “relatively thin culture.” [3] There is a paradigm shift occurring within Caribbean academic contexts, and I believe it lies between a regional focus and a recognition focus, because there is an embodied epistemological value in knowing and living in enclosure.

Audre Lorde, Sylvia Wynter, M. Jacqui Alexander, Deborah Thomas, and Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez offer us insights from their embodied experience standing, amongst others, in what I see as Caribbean thought. For instance, in “When We Come to Anthropology, Elsewhere Comes with Us,” Ashanté Reese discusses her entrance into anthropology by way of ethnography and Zora Neale Hurston’s example. She states, “I, like many of us, came into the discipline from epistemological elsewheres that we cannot and often do not want to shed. I, like many of us, do ethnography from a place in which distinctions between my ‘self’ and the ‘other’ feel futile. We do ethnography as if our lives depend on it. Because they do.” Here Reese exemplifies the doing of an ethnography from enclosure, what doing ethnography from redaction might look like, and–more–importantly what the stakes are.

[Sarah Bruno, Redaction of La Vida, 2024]

Scholars who themselves have not been or are not in enclosure might be prescriptive, and this is not to say they won’t articulate thinly veiled infrastructural and ethnographic problematics or offer reparative solutions. Ethnography from enclosure or from elsewhere makes legible the interstices of harm and also how people endure. For example, Leniqueca Welcome, in “On and In Their Bodies,” writes, “Gender-based violence, inter/intra-community gun violence, and state violence are often treated distinctly in analysis. Yet as the women convened in the shop and shared their experience of black poor womanhood in Trinidad, they revealed how these different forms of violence are felt and carried together, thereby inviting us to think more about their entanglements than their divergences” (39-40).

Studies on the Caribbean might separate these types of violence, however, being trained in Caribbean thought and being an active agent of such thought, Welcome sees the relations. [4] She answers the call that Reese (2019) puts forth, “With and from our elsewheres, we challenge colonialist practices of carving up and dismembering. With our refusals, we commit to being whole.” There is value in keeping some discourses out of the everlasting and ever reaching archive, keeping some discussions in house. However, that elicits an embodied preoccupation and method of kinship amongst the people we write about, a reverence to do what Welcome urges us to do: “may we take a breath on this ground on which moments of precious life are lived now, and let it help us find an opening” (58).

There is also something to be said about having skin in the game. Here I could be referencing either the phenotypic or metaphysical flesh that was at stake when empires built and continue to build their economic wealth indebted to the embodied repercussions of colonialism. But beyond that, there is something about having a personal stake in the words on a page. When discussing abolitionist anthropology and its potentialities as well as some of its co-optations, Savannah Shange in “Abolition in the Clutch” with heavy discernment says, “embedded in the logic of this (good) faith query is a twin assumption: a) anthropology and abolition are reconcilable, b) my spiritual investments include an academic discipline. Wrong on both counts, but that is on me” (187). I believe one has to develop convictions to build a humanistic intellectual life, and to limit those convictions to a faulty academic discipline is an act of disservice.

A discipline is loyal to no one, only to whichever ethnographic truth is deemed relevant or convincing. To do work on Puerto Rico or write ethnography on Afro-Puerto Ricans, does not mean we are automatically in solidarity and the onus is on me to clarify that. To love methodologies that have been violent and remix them into something that can rectify the redaction, that brings forth that which was obscured, is an elsewhere ethnographic type of labor.

Notes

[1] Here I am thinking alongside Tiffany Lethabo King in The Black Shoals (2019) in her re-articulation of settler colonialism as conquistador colonialism so as to not erase the violence and genocidal intentions on which empires are built. See also Christina Sharpe. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016, as well as Deborah Thomas. Political Life in the Wake of the Plantation: Sovereignty, Witnessing, Repair. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019.

[2] Weathering is the embodied result of constant antiblack violence. Christina Sharpe elucidates this intervention via the detrimental extended atmospheric exposure that results in the chipping of sediment.

[3] I am meditating on the methodologies for Black life and black livingness as put forth by Katherine McKittrick in Dear Science (2021).

[4] As a part of the Diaspora Solidarities Lab, we are anchored in Black and Caribbeanist thought, one of the key bridging conceptual tethers being Édouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation (1990).

References

Briggs, Laura. Reproducing Empire Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2003.

McKittrick, Katherine. Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

Reese, Ashanté. “When We Come to Anthropology, Elsewhere Comes with Us.” Anthropology News. February 20, 2019.

Shange, Savannah. “Abolition in the Clutch: Shifting through the Gears with Anthropology.” Feminist Anthropology 3-2 (2022): 187-197.

Welcome, Leniqueca A. “On and In Their Bodies: Masculinist Violence, Criminalization, and Black Womanhood in Trinidad.” Cultural Anthropology 39-1 (2024): 37–63.

Sarah Bruno is from the southside of Chicago and is an incoming Assistant Professor in the departments of English and African and African American Studies at Michigan State University. She is a Diaspora Solidarities Lab postdoctoral fellow in the English Department at MSU and co-director of Taller Entre Aguas, a microlab dedicated to the Black Puerto Rican life and data. This year she is a Visiting Scholar in the Center for Africana Studies at John Hopkins University. She is currently on her first book-length manuscript, Black Rican Refusal: Decolonial Postures, Dexterity, and Bomba.